Executive Summary | National Landscape | Phone Rates for Prisons in Nebraska | Emerging Issues Needing Further Study | Attorney Calls in Nebraska | Recommendations | Conclusion

Introduction

The ACLU of Nebraska is a non-profit, non-partisan organization that works to defend and strengthen the individual freedoms and liberties guaranteed in the United States and Nebraska Constitutions through policy advocacy, litigation and education. We serve thousands of members and supporters stretching across the great state of Nebraska.

Criminal justice policies in Nebraska and across the United States have created a system of mass incarceration which hurts our communities and disproportionately impacts low-income families and communities of color. Imprisonment is a brutal and costly response to crime that traumatizes incarcerated people and hurts families and communities. It should be the last option, not the first. Yet the U.S. incarcerates more people, in both absolute numbers and per capita, than any other nation in the world. For the last four decades, this country has relentlessly expanded the size of our criminal justice system, needlessly throwing away too many lives and wasting trillions of taxpayer dollars.

Nebraska has a role to play in reducing America’s addiction to incarceration and providing programs that help those accused or convicted of a crime to turn their lives around.

Acknowledgments

Grateful appreciation to Senator John McCollister for introducing LR 208 and Senator Patty Pansing Brooks for introducing LR 198 to study the question of how high phone rates are impacting children of incarcerated parents.

Research and data collection by Nathan Calvin, Grinnell College, Class of 2018.

Today, 5.1 million children have a parent behind bars. In Nebraska, that’s 41,000 young people or about one in ten children who have a parent who has been or is currently incarcerated.[1] For these kids, losing a parent to incarceration can be as traumatic as losing a parent to death or divorce.[2] For families with a loved one in jail or prison, phone contact is often the only way to connect on a routine basis. Over half of the Nebraskans in county jail are not yet convicted of any crime—they simply lack the money to post bond and go home as they await their trial.[3] They aren’t there briefly—a nonviolent offender who cannot post bond spends an average of 48 days in jail.[4]

“EMMA” | A Nebraska Story

Emma’s son was away at college when he was approached by another student asking to buy a gram of marijuana—in other words, enough to roll between one and three joints. Her son wasn’t normally a dealer, but he had pot and agreed to sell it. The other student then revealed himself to be an undercover police informant. Emma’s son had no prior criminal history, but because he was charged with a felony, he was given a high bond the family can’t afford.

As of the writing of this report, Emma’s son has been in the county jail for five weeks.

Emma lives 60 miles from the jail and visits twice a week. For the other days, she must rely on the phones to communicate with her son. So far, Emma has already spent over $300 on phone calls. “I constantly put money on his books, but I definitely speak less to him just because I can’t afford to call as much as I want. This $20 drug transaction is costing the county a lot of money to house him in jail and is costing me hundreds of dollars to stay in touch to be supportive. He’s never been in trouble before and he’s having serious depression so it’s important that I stay in touch. I don’t understand how this is benefiting anyone.”

Incarceration already falls disproportionately on the poor and on communities of color. While only one in ten Nebraskans is a person of color, five of ten pretrial detainees in Nebraska county jails are people of color.[5] The burden also disproportionately affects parents of young children. Federal studies show that 60% of women in prison are mothers of a child under 18.[6]

The ACLU of Nebraska has received repeated complaints from families struggling financially to stay in touch with an incarcerated family member. We have also received multiple reports from attorneys who aren’t able to have a confidential phone call with their clients in jail. Over the summer of 2017, ACLU of Nebraska used open records requests to learn more about the cost of calls from behind bars. Our findings unveiled a statewide problem of county jails charging exorbitant rates arising from kickback agreements in which county officials grant private for-profit companies monopoly contracts in exchange for a cut of the profits. In contrast, the state Department of Correctional Services has banned all phone commissions and set a clear standard for county jails to follow.

If you’re not incarcerated, a call home to your family might cost a few cents a minute or just be bundled into your monthly package. But people detained in county jail are charged up to $19 for a 15-minute phone call. Because county jail detainees rarely or never have the chance to earn money behind bars, the financial burden of these unconscionably high rates falls entirely on their families.

For-profit prison phone companies charge sky-high rates to incarcerated people and their families, making it too expensive for families to stay connected. The financial burden often falls on families of incarcerated people because prisoners cannot afford the outrageous charges. Poor people are grossly over-represented in the exploding prison population—national studies show that between 60 to 90% of prisoners are indigent and qualify for a public defender because they are poor.[7] When a parent is incarcerated, that almost always means a major loss of household income, which exacerbates the family’s financial circumstances. If the family doesn’t have gas money for in-person visits or inflated phone rates, their financial hardship prevents prisoners and their families from communicating at all.

Phone companies should not be able to profit off incarcerated people trying to be good parents or good family members. Steep prices mean many prisoners will not be able to call home as often as they would choose. This is no way to achieve our shared goal of public safety. At least 95% of people currently in prison will return to our communities after they complete their sentences.[8] The average Nebraska prisoner will serve two to six years before being released home.[9]

When people keep in touch with their families while in prison, studies repeatedly show they are less likely to commit new criminal offenses after returning to the community and less likely to wind up back behind bars. Keeping family ties strong not only prevents recidivism—it also strengthens the mental health and well-being of the children left at home.

We should adopt policies that help them succeed after their sentences—not encourage them to fail. When people keep in touch with their families while in prison, studies repeatedly show they are less likely to commit new criminal offenses after returning to the community and less likely to wind up back behind bars.[10] Keeping family ties strong not only prevents recidivism—it also strengthens the mental health and well-being of the children left at home. We know there are many children impacted by parents in jail–approximately seven in ten women under correctional sanction have minor children at home.[11] By ensuring family contact, officials can secure taxpayer savings, public safety gains and better outcomes for the families.

Who profits from this present destructive system of jail phone service? The phone companies and, sometimes, the county jail. In this market, specialized phone companies compete for the right to exclusive contracts in each jail. In exchange, the county gets a “commission” by the phone company, and it encourages jail officials to inflate calling rates rather than keep them affordable. One FCC commissioner called this system “the clearest, most egregious case of market failure” she had seen in sixteen years as a regulator.[12]

“Every day, an inmate makes a call, a family member receives a call, and someone profits from the call made...[we’re] paying the highest verifiable commissions available.” – Screenshot and quote from an actual Encartele advertisement.

The for-profit corporations aren’t hiding the financial gain involved: they actually advertise the kickback system. In the promotional sales video created by Nebraska-based company Encartele, the voiceover says “Every day, an inmate makes a call, a family member receives a call, and someone profits from the call made...[we’re] paying the highest verifiable commissions available.”[13] The video depicts a grandmother picking up the phone while a cartoon sheriff is shown shaking a money tree raining dollar bills.

While the companies win, everyone else loses. Prisoners and their families suffer financial hardship or fall out of touch. As a result, the community as a whole is likely to suffer when the jails return them to society more alienated and less connected to positive influences.

Telephone access in jail is also important for ensuring people facing criminal charges get their fair day in court. If you’re locked in a jail cell facing serious charges, a telephone call to your lawyer may be your only hope to clear your name and get back to your job and family. But, given the high rates for phone calls described above, even calling a lawyer while in county jail can be very difficult.

Our survey revealed that a few counties are following best practices by providing appropriate free and confidential calls to a lawyer. However, other counties impose the same crushingly expensive rates for even a call to the attorney appointed to an indigent person. We’ve received reports of people unable to leave messages for their lawyer because they were collect calls, calls that dropped in the middle of a conversation if the call lasted longer than the amount the prisoner had on their card, and jails providing no private space for making a confidential attorney call.

“The ‘Profiting Off Lifelines’ report adds to mounting evidence showing that children pay a hidden and significant cost when it comes to our adult justice system. All children need meaningful contact with their parents, especially during stressful circumstances, and policies that permit financial exploitation of parent-child relationships are contrary to Nebraska values.”

Julia Tse, Policy Coordinator, Voices for Children in Nebraska

Spurred by a grandmother’s complaint to the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), and after a lengthy study of egregiously high phone call costs for people behind bars, the FCC issued regulations in 2013 and 2015 to cap the cost of prison and jail phone calls.[14] The FCC set different rates for county jails (which house pretrial detainees not yet convicted of any crime as well as people convicted with a short sentence) and for state prisons (which house people convicted with a longer sentence). By July 2017, the proposed FCC caps on collect calls within a state (intrastate) were to be:

- 36 cents per minute for county jails that housed between 0-349 people

- 33 cents per minute for county jails that housed between 350-999 people

- 32 cents per minute for county jails with over 1,000 people

- 13 cents per minute for all state prisons.

For collect calls between more than one state (interstate), there was a hard cap of 25 cents per minute regardless of facility size. The FCC also placed caps on the surcharges and transaction fees telecommunications companies could impose.

Before the rate caps could go into effect, for-profit telecommunication companies challenged these intrastate regulations in court, arguing they violated the Commerce Clause of the Constitution. The federal court agreed, leaving the interstate regulations standing but striking down intrastate rate caps.[15] This ruling was about the limits of the FCC’s authority, not the wisdom of the regulations and in no way an endorsement of the status quo, as the court noted these charges “raise serious concerns” and called some of the rates charged by jails and prisons “extraordinarily high.”

The FCC rate cap of 25 cents per minute on prisoner phone calls made from one state to another still stands, but most prisoners are serving time in their home state, which is not covered by the FCC rate cap order. In order to stop the abuse, it will take action by the state legislature to emulate the FCC and end this predatory practice for all county jail phone calls.

The end of the FCC intrastate rate caps has passed the regulatory baton to the states. Now, state by state, we must take action to tailor remedies against these abusive practices.

State prisons

Nebraska state facilities have already stepped up to this challenge. The Nebraska Department of Correctional Services (NDCS) has a regulation forbidding commissions “in the interest of making inmate calling as affordable as possible.”[16] As a result of this decision, Nebraska state prisons boast one of the lowest call prices in the nation, at 5 to 10 cents per minute depending on whether it is a local call or not. This means a prisoner can call home anywhere in Nebraska to connect with their family for 15 minutes and it will only cost $1.50. Even an indigent prisoner without any funds has a monthly option to choose either five free stamps or a free $2.50 calling card.[17]

One human rights organization has ranked Nebraska state facilities as the best phone rate in the country.[18] Additional research has shown the prices in Nebraska are not as low as indicated in that ranking, but Nebraska rates are clearly among the lowest nationwide. See Appendix for state phone rates. Our state prison system ban on kickbacks or commissions should be a model for all county facilities.

County jails

In contrast, Nebraska county jails are permitted to receive unlimited commissions from phone companies, have no limits on the rates for intrastate calls, and have no caps on surcharges. This is particularly troubling since county jails are shorter-term facilities than prisons, and approximately one half of the county jail population are pretrial detainees who are actively defending cases in which they are presumed innocent but are unable to post bail to go home. As last year’s ACLU of Nebraska report on debtors’ prisons revealed, the average person charged with a non-violent offense will spend 48 days in jail before his or her case is decided.[19]

Pretrial detainees have a heightened need to contact their attorneys to prepare their case but, as discussed later in this report, many jails impose the same costs for a call to a lawyer as they do for a call home. In the summer of 2017, the ACLU of Nebraska sent out open records requests to all 64 county jails in the state asking for the rates they charged prisoners and detainees.[20] A copy of our open records request letter is in the Appendix.

In comparison to the $1.50 a state prisoner will pay for a 15 minute call, we discovered county detainees may expect to pay between $2 and $20 for that same 15 minute call, depending on the county in which they’re housed.

The results of our survey were startling. In comparison to the $1.50 a state prisoner will pay for a 15 minute call, we discovered county detainees may expect to pay between $2 and $20 for that same 15 minute call, depending on the county in which they’re housed.

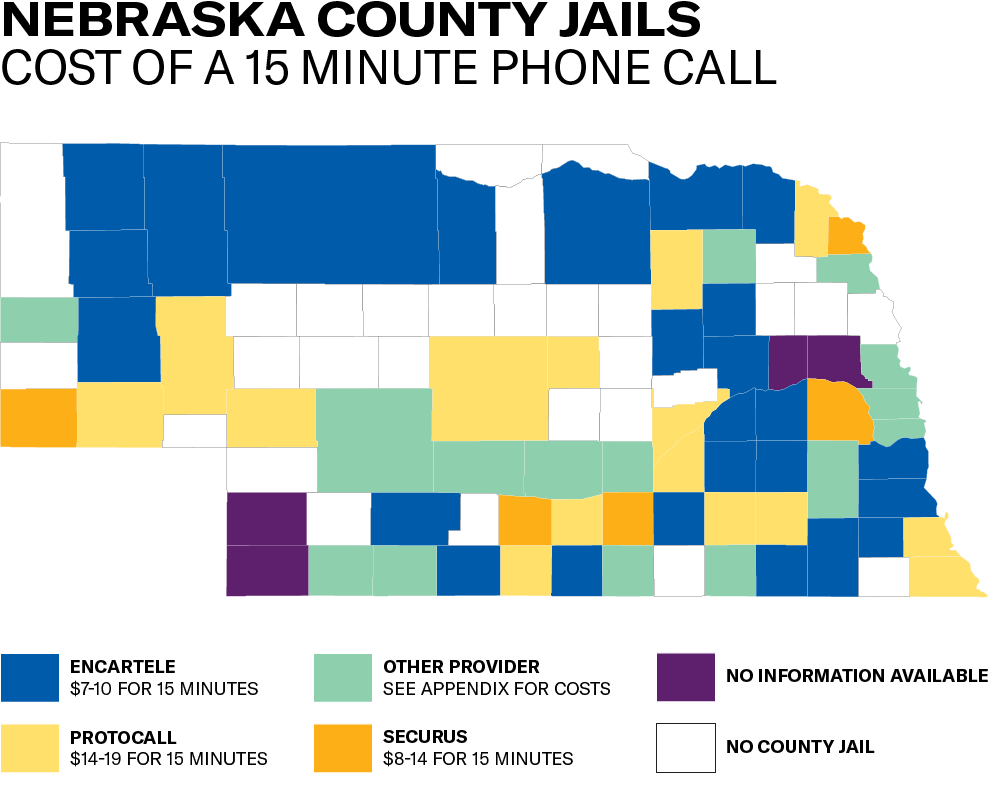

Nebraska counties are using several for-profit companies based throughout the country. The three largest providers in the state are:

- Encartele, based in Nebraska (26 counties): average cost $7-10 for 15 minutes

- Protocall, based in Kansas (15 counties): average cost $14-19 for 15 minutes

- Securus, based in Texas (5 counties): average cost $8-14 for 15 minutes

These initial rates that prisoners and pretrial detainees are charged do not include additional ancillary fees that many of these companies also impose. In the FCC rate cap lawsuit the court found that 38% of the for-profit prison phone call company revenue is generated by ancillary fees.[21] Some of the extra charges we identified in Nebraska include:

- $2 a month just to open and maintain an account (Protocall)

- $2 a month to receive a paper bill (Global Tel*Link)

- $3 for each call through any wireless phone (Protocall)

- $3 to pay by credit card (Global Tel*Link)

- $8 to add funds to your prepaid account (Securus)

A county-by-county breakdown of the cost of calls can be found in the Appendix. Most of these for-profit companies have a long history of being sued for poor quality service or exorbitant fees.[22]

Table A | Counties with the Highest Income from Jail Phone Calls

| County |

County

Income from

Jail Calls |

County

Budget

2014-2016 |

Population

Rank

2016 Estimate② |

Monthly Cost to Prisoner

Making four 15 minute calls a week |

% of Weekly Income

for a family of four receiving

SNAP benefits③ |

Gallons of Gas

for the same cost as monthly phone calls④ |

| Douglas

|

$617,062

|

$320,756,053

|

1

|

$41.76

|

2%

|

17

|

| Lancaster

|

$397,566

|

$140,932,017

|

2

|

$50.40

|

3%

|

22

|

| Scotts Bluff

|

$77,265

|

$29,432,616

|

7

|

N/A

|

N/A

|

N/A

|

| Sarpy

|

$38,464

|

$90,238,404

|

3

|

$41.76

|

2%

|

17

|

| Lincoln

|

$37,470

|

$20,798,297

|

8

|

$99.68

|

4%

|

40

|

| Platte

|

$33,898

|

$23,891,430

|

10

|

$99.68

|

4%

|

40

|

| Dawson

|

$30,152

|

$23,399,633

|

13

|

$96.48

|

4%

|

39

|

| Saunders

|

$28,028

|

$36,217,734

|

15

|

$168.16

|

6%

|

68

|

| Saline

|

$22,139

|

$10,880,133

|

20

|

$318.24

|

12%

|

129

|

| Buffalo

|

$20,461

|

$26,348,262

|

5

|

$160.96

|

6%

|

65

|

① www.nebraska.gov/auditor/reports/index.cgi?county=1

② Annual Estimates of the Resident Population: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2016, U.S. Census Bureau, Population Division

③ http://dhhs.ne.gov/children_family_services/Pages/fia_guidelines.aspx

④ https://www.bls.gov/regions/mid-atlantic/data/averageretailfoodandenergy...

The amount of income that jails make from the calls compared to the actual costs of the calls varied widely from county to county. Some counties received income of a couple hundred dollars last year. Other counties reaped astonishing amounts of money from the families of poor people totaling $1,407,327.25 across the state (counties with highest revenue from jail phones seen in Table A). For example, Lancaster County reaped $397,566 in 2016 and Douglas County took in $617,062 in 2016. Incarceration should never be a profit generator for the government—especially when half of those behind bars in county custody are pretrial detainees who are presumed innocent as they seek to defend themselves against a pending case. But this jail call money-making scheme is a modern twist on the Victorian for-profit debtors’ prisons.

Table B | Counties with fees beyond the per-minute charge

| County/Counties |

County

Income from

Jail Phones |

| Adams, Dakota, Kimball, Phelps and Saunders Counties |

Prepaid Calls: $2.99 per month

Transaction fee: $7.95

Collect Calls: $3.49 per month |

| Antelope, Cheyenne, Custer, Dixon, Fillmore, Garden, Hamilton, Harlan, Kearney, Keith, Merrick, Nemaha, Richardson, Saline, Valley, and Washington Counties |

Monthly Fee: $2.00

Per call fee for phones (including wireless) without a billing arrangement: $3.00 |

| Douglas County |

Automated Payment to Card: $3.00

Paying by Live Operator $5.95

Paper Bill $2.00 |

| Lincoln County |

Deposit: $3.00 |

Table C | Summary of County Jail Costs for a 15-minute call

| |

Average |

Highest |

| LOCAL |

|

|

| Collect |

$8.10 |

$14.85 |

| Pre-paid Debit |

$5.70 |

$8.75 |

| Pre-paid Collect |

$7.66 |

$14.85 |

| INTRALATA |

|

|

| Collect |

$9.23 |

$14.85 |

| Pre-paid Debit |

$6.34 |

$11.50 |

| Pre-paid Collect |

$8.44 |

$14.85 |

| INTERLATA |

|

|

| Collect |

$9.54 |

$15.10 |

| Pre-paid Debit |

$6.66 |

$14.30 |

| Pre-paid Collect |

$8.47 |

$14.85 |

| INTERSTATE |

|

|

| Collect |

$3.98 |

$16.41 |

| Pre-paid Debit |

$3.35 |

$7.50 |

| Pre-paid Collect |

$3.75 |

$7.50 |

“Cristie” | A Nebraska Story

Cristie’s fiancé was held as a pretrial detainee on federal drug charges in a county jail for almost a year. In-state rates were costing her about $6 per 15 minutes, even though calling from an out of state number would have cost $4 per 15 minutes. “It’s not fair—they know your family is likely to be closer by, so they charge more to call down the street than it costs to call across the continent.” Her fiancé was experiencing intense anxiety and depression at the outset and was relying on her to help locate witnesses his attorney could then contact. “I ended up paying over $800 to stay in touch with him. The kids and I had only my income, and there were months when I had to tell him he wouldn’t hear from us until my next payday. It especially impacted my 14-year-old who knew she would have been in touch if only we’d had more money.”

There are three areas our investigation revealed will need further study.

State Prisoners in County Facilities

State prisoners in state facilities have commission-free telephone services. However, it appears that state prisoners who have been transferred to county jails due to overcrowding are paying the same exorbitant phone rates as the county detainees. According to the most recent NDCS data, there are 94 state prisoners housed in county jails.[23] Since state prison sentences can be many years long, these prisoners and their families may have to pay these much higher rates for years.

Video Calling

Video calling services have emerged as an option in some Nebraska county jails, including Lancaster County.[24] These systems, which the companies describe as “video visitation,” are advertised as being similar to Skype or Facetime video calls, although the actual calls are reportedly lower quality and less reliable.[25] Instead of treating video calls as a supplement for in-person visitation and phone calls, some jurisdictions have experimented with prohibiting all in-person visits, leaving families with only telephone contact or video calls—both of which are, not coincidentally, typically provided by the same telephone provider. The rates and surcharges for video calls are completely unregulated, and like telephone calls, similar commission-based profit incentives are often involved. Studies have concluded that the video call rates are very high nationwide.[26] Recent news reports suggest a similar high cost in Nebraska[27], but further study is necessary to identify all the rates, surcharges and fees associated with video calling systems.

Accommodations for Prisoners who are Deaf

Prisoners who are deaf most commonly use a videophone to make calls: the video screen allows the person to sign to their loved one or to an interpreter who relays the prisoner’s words to the family member. Nationwide, many correctional facilities still only have outdated TTY systems where an operator reads the typed words of the person who is deaf. It is a slow and cumbersome process that does not promote effective communication.[28] We did not investigate the best modern technology or policies needed to ensure that a county jail detainee who is deaf may have meaningful and reliable contact with an attorney or a family member. This impacts a significant number of Nebraskans—according to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, approximately 6% of prisoners have a hearing disability.[29] Failure to provide appropriate accommodations may trigger a lawsuit like those that have been filed successfully in Idaho, Virginia, Florida, Maryland and Kentucky.[30]

“Farrah” | A Nebraska Story

Farrah is a refugee and naturalized US citizen. Her adult nephew was arrested for a nonviolent misdemeanor earlier this summer, and because he is not yet a citizen, he worries he might be facing deportation in addition to a criminal conviction. Farrah and her nephew’s mother live in Lincoln, but the young man is housed in a rural jail in central Nebraska that is a 90-minute drive each way. Since it’s difficult to travel that far, the family relies primarily on phone calls. Farrah reports her nephew is having a very hard time in jail: the facility is overcrowded, there is no open-air exercise, and many guards and prisoners are hostile to him because he is a minority. He is desperately worried about what will happen with his criminal charge as well as his immigration case, so his family tries to talk to him as much as possible to buoy up his spirits. “We pay about $6 per call, plus $10 every month to cover all the other fees. He tells us he hasn’t seen the sun for weeks, and we are his only ray of hope when we are able to afford that call.”

County jail detainees don’t just need to talk to their families—they also need to call their lawyers. The vast majority of county jail detainees are represented by public defenders due to their indigent status. In greater Nebraska, public defenders and court appointed lawyers may be required to cover territory across several counties. Their far-flung clients may be many hours apart from each other and the attorney’s office, so telephone calls are less burdensome than traveling for personal interviews. Each prisoner needs to be able to communicate with his or her attorney to prepare for trial and confer about their case. That’s a tall order when the cost of the call is very high or when the client can’t even leave a voicemail or speak without the fear that the sheriff might be listening in.

The Sixth Amendment guarantees the right to counsel for people charged with criminal offenses. It includes the right to have a competent defense that has not been compromised by government eavesdropping or rendered unaffordable by the greed of jail officials.[31] Confidential discussions between an attorney and client are the bedrock to a meaningful defense and are privileged communications.[32] Courts have been particularly protective of a pretrial detainee’s right to adequate and confidential phone calls with their attorney because these rights are essential to receiving a fair trial, and a pretrial detainee is presumed innocent. The Eighth Circuit, which is the federal circuit court of appeals covering Nebraska, has ruled “Pre-trial detainees have a substantial due process interests in effective communication with their counsel . . . when this interest is inadequately respected during pre-trial confinement, the ultimate fairness of their eventual trial can be compromised.”[33]

Given this body of caselaw, jails risk expensive civil rights litigation if they fail to provide adequate confidential phone calls with attorneys that are free for all indigent people. Otherwise, when a pretrial detainee is trying to decide whether to spend her few dollars on a call home to talk to her children or call her lawyer to prepare for trial, we’ve set an impossible choice before her.

Our survey revealed significant variance in internal rules in place to protect the attorney-client relationship. Thirty-one counties have no written policies governing attorney-client call confidentiality. Only twenty seven counties provide free calls to attorneys. Eight other counties permitted free local attorney calls or free calls to public defenders while charging for all other attorney calls. See Appendix for a complete breakdown of policies and costs for attorney-client calls.

Confidentiality

The ACLU survey on attorney-client calls was prompted in part by reports from lawyers who have had their conversations with incarcerated clients recorded without their knowledge. Such recordings infringe on the attorney-client privilege, which is a foundational principle of our legal system and is essential to providing a competent defense.

In one example, the court appointed an attorney to represent a defendant facing serious felony charges, but the attorney’s office was an hour and a half away from the Hall County jail where his client was housed. Given the distance, the attorney had to rely on phone calls to prepare for the upcoming trial. In the routine discovery process, prosecutors provided the attorney with a CD containing all his client’s phone calls from the jail. When the attorney reviewed the CD, he was shocked to find he was listening to his own calls with his client: in fact, the sheriff had recorded 59 phone calls between the attorney and client and provided those recordings to prosecutors. The attorney successfully moved to seal the phone calls and disqualify all current prosecuting attorneys in order to prevent the prosecution from gaining an unfair advantage from the confidential attorney conversations.[34] However, the whole episode raises troubling questions about what other attorney-client calls in Hall County or other jails might be improperly recorded and shared with prosecutors.

“My clients at [undisclosed] county jail have one phone to use: a pay phone on the wall in a common area without any privacy. I need to ask them questions about their upcoming case but sometimes they’re scared to answer me because other prisoners or county jail staff are standing nearby.”

Another attorney told us, “My clients at [undisclosed] county jail have one phone to use: a pay phone on the wall in a common area without any privacy. I need to ask them questions about their upcoming case but sometimes they’re scared to answer me because other prisoners or county jail staff are standing nearby.”

While jails may have legitimate reasons to record prisoner conversations in some circumstances, such as when a prisoner is attempting to use the phone system to threaten witnesses or coordinate illegal activities, the jails must have safeguards in place to ensure attorney conversations are not caught in a recording dragnet.

Most jails reported they have no written policy on the issue. A few reported anecdotally that while they have no written policy, and despite the fact they confirmed they record all calls, they promise they do not listen to a recording once they realize it is between an attorney and their client. However, this is no substitute for actually installing a system designed to safeguard the attorney-client privilege—especially since these phone companies specialize in prison and jail phone systems. Securus, the phone provider in five Nebraska county jails, is currently being sued in a class action in California for continuing to willfully record attorney-client phone calls despite repeated warnings of the problem.[35] They’ve also been caught recording calls in Missouri in what has been called the “most massive breach of the attorney-client privilege in modern U.S. history.”[36]

In some counties, the telephone system offers the option to put attorneys’ phone numbers on a “do not record” list. However, several county officials admitted their list of attorneys was far from comprehensive and that it was likely some attorneys were falling through the cracks and being recorded. Only a few counties were following best practices in that they have a phone that is physically separate and offers a consistent non-recorded line for attorney calls.

As the Nebraska Supreme Court Lawyer’s Advisory Committee on ethics has said, “A defendant held in a government detention facility, like any other client, is entitled to expect that his communications with his lawyer will be confidential” and “mere assurances from the government” are not adequate to safeguard confidentiality.[37] Lawyers representing Nebraskans in county jails deserve clear statewide standards to ensure there is no eavesdropping by government officials.

“I expect the prosecutors to do everything they can to try their case and win. I also expect prosecutors to play fair and follow the rules. I’ve been shocked to learn how often the basic principles of attorney-client privilege aren’t being followed. When a jail passes along information from a confidential phone call I have with my client to the prosecutor, I can’t effectively represent my client. Cutting corners isn’t how our judicial system should work,”

Ben Murray

Germer Murray & Johnson

Attorney call cost

Our survey revealed that the cost of attorney calls varies widely across the state. Some counties confirmed that they always charged attorney calls at the same rate as a call home. Other counties had exceptions and allowed free calls to public defenders while still charging for calls to any private attorney. The majority of counties had no written policies about the cost of calls to legal counsel.

One attorney who is appointed to represent indigent clients in a large five-county area told us “I regularly have difficulty getting calls from my clients. Even though I was court-appointed precisely because the client has been found to be poor, the county jail says, ‘Your client needs to pay for it on his own or he can call you collect.’ That just shifts these ridiculously expensive calls to me and I’m not being reimbursed by the court. Yet I can’t conduct my business by driving over an hour every time I need to communicate an update or pose a question to my client.”

Another attorney shared, “my client started in one county jail that offers free calls to attorneys, but when he was moved to a county without free lines, I contacted the Sheriff to request phone access. I was told ‘this isn’t our problem and we won’t do it. You’ll need to work it out somehow.’ I could drive the hour and a half to see him, but ironically I’ll end up billing that time to the county so there is no savings to deny this man his attorney calls.”

There are several reasonable ways to reform phone access for prisoners in county jail. Nebraska county jails have the excellent model policies from the state NDCS that could be adopted county-by-county. State policymakers should pass legislation to ensure consistent access to family and legal counsel.

SOLUTION: Public Service Commission regulations

The Nebraska Public Service Commission (PSC) could study the issue and, like the original FCC regulation, issue a regulatory rate cap and restrictions on ancillary fees that would apply to all county facilities. The PSC would first need statutory authority to regulate in this arena.[38] New Mexico has already enacted such a jail telecommunications rate regulation through their state public service commission.[39]

SOLUTION: Nebraska Jail Standards Board regulations

The Nebraska Jail Standards Board could be charged with the task of setting a regulatory rate cap and restrictions on ancillary fees for all county jail facilities. The board would also be best positioned to draft model policies regarding protecting the confidentiality of attorney client calls.

SOLUTION: County Board action to ban commissions

County boards could prohibit commissions from phone contracts, following the model of the Nebraska Department of Correctional Services. The Nebraska Association of County Officials could provide model policies to ensure appropriate rates and fees that reflect the actual cost of providing telephone service.

SOLUTION: State statute ban on commissions and rate cap

The Legislature could pass a state law that resembles the “no commissions” rule used by the Nebraska Department of Correctional Services. Legislative reform of the for-profit telecommunications industry is already gaining momentum on a national scale. Illinois[40], Michigan[41], Mississippi[42], New York[43], New Jersey[44], New Mexico[45] and several other states have passed laws that capped rates and ended the practice of taking commissions in their state prisons. Legislation is pending in Montana[46] to make all attorney phone calls free. The best model is from New Jersey, where a 2016 bipartisan bill affecting both state prisons and county jails banned commissions, surcharges and fees, and capped in-state call rates at 11 cents per minute.[47]

A state law rate cap could follow the original FCC model with different rates depending on the size of the jail to account for the lower profitability in smaller rural counties.

SOLUTION: Further legislative study of impact on prisoners who are deaf, state prisoners in county care, and the cost of video calling systems

Our investigation was limited in scope regarding the questions about true phone access for prisoners with disabilities (especially those who are deaf); how state prisoners housed in county facilities due to overcrowding are charged; or how the emerging trend of video calling systems is impacting indigent families. A legislative resolution to study these issues further may help illuminate areas ripe for additional reform.

Expensive phone rates and policies in county jails aren’t just affecting the men and women behind bars—these practices also impact families and children. Cutting off lifelines to children, to families and to lawyers not only endangers the wellbeing of the incarcerated person but also harms their family members and threatens public safety by increasing the risk of recidivism.

Additionally, recording attorney phone calls and making it impossible for indigent people to call their public defenders undermines the legitimacy of the criminal justice system.

Jail phone service is a classic case of market failure, in which regulators must step in to ensure fair pricing and adequate functionality. In this broken “market,” specialized phone companies use monetary commissions to entice government officials to sign monopoly contracts. Meanwhile, the people who actually use these telephone systems—incarcerated people, their families and attorneys—are shut out of the contract negotiations and must suffer the inflated phone rates and limited functionality that result from a market that prioritizes commission revenue over price and quality of service. Common sense reforms to guarantee confidential attorney contact and limit the cost of calls to the actual cost of the service are needed to ensure a better result for those behind bars, their families and our communities.

[7] Marea Beeman, Am. Bar Ass’n, Using Data To Sustain And Improve Public Defense Programs 2 (2012). http://texaswcl.tamu.edu/reports/2012_JMI_Using_Data_in_Public_Defense.pdf

See also Bureau Justice Assistance, Dep’t Justice, Contracting For Indigent Defense Services 3, n.1 (2000), available at www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/bja/181160.pdf and Caroline Wolf Harlow, Bureau Justice Statistics, Dep’t Justice, Defense Counsel In Criminal Cases 1 (2000), available at http://bjs.ojp.usdoj.gov/content/pub/pdf/dccc.pdf (over 80% of people charged with a felony in state courts are represented by public defenders).

[9] Nebraska Department of Correctional Services Annual Report (2014), p. 47

[20] Although there are 93 counties in Nebraska, not every county has a jail.

[30] Marshall Project, Id. Cases are also still pending in Michigan, Illinois and Massachusetts.

[31] See, e.g., Bounds v. Smith, 430 U.S. 817, 828 (1977) (prisoners have a constitutional right to access the courts) and Lewis v. Casey, 518 U.S. 343, 355 (1996) (prisoners are entitled to court access)

[32] See, e.g., Fisher v. United States, 425 U.S. 391, 403 (1976) and Weatherford v. Bursey, 429 U.S. 545 (1977)

[33] Johnson-El v. Schoemehl, 878 F.2d 1043, 1051 (8th Cir. 1989)

[34] State v. Foster, Order, Case. No. CR14-10 (Nuckolls County District Court).

[38] See Neb. Rev. Stat. 86-139 regarding the PSC scope of authority.

Date

Thursday, November 30, 2017 - 9:00am

Featured image

Show featured image

Hide banner image

Related issues

Smart Justice

Documents

Show related content

Tweet Text

[node:title]

Share Image

Type

Menu parent dynamic listing

Featured video (deprecated):

Style

Standard with sidebar

Introduction | Key Findings | Nebraska Women’s Prisons | The Number of Women in Prison Is on the Rise | Women of Color are Overrepresented | Unique Pathways to Prison | Parenting in Prison | Health Care for Incarcerated Women | Recommendations for Reform | Conclusion

The ACLU of Nebraska is a non-profit, non-partisan organization that works to defend and strengthen the individual rights and liberties guaranteed in the United States and Nebraska Constitutions through policy advocacy, litigation and education. For over fifty years, the ACLU of Nebraska has been a constant guardian for freedom and liberty fighting for the civil rights and civil liberties of all Nebraskans. The ACLU of Nebraska intentionally prioritizes the needs of historically unrepresented and underrepresented groups and individuals who have been denied their rights; including people of color, women, LGBT Nebraskans, persons incarcerated and formerly incarcerated, students, and people with disabilities.

Nebraska's criminal justice policies have created a system of mass incarceration. This hurts our communities and disproportionately impacts low income families and people of color. Existing conditions violate the Eighth Amendment's protection against cruel and unusual punishment and do not provide for meaningful transition back into our communities and our economy. The ACLU is leading the way to rethink and reform these policies and conditions though our campaign for Smart Justice to protect individual rights, reduce the taxpayer burden, and make our communities safer.

Existing "tough on crime" policies, particularly around punitive drug policies, have failed to achieve public safety while putting an unprecedented number of people behind bars and eroding constitutional rights. This system also erodes economic opportunity, family stability, and civic engagement during and after incarceration. In many instances, a criminal record becomes a life-long barrier to accessing basic human needs and ensuring individual and family stability.

The Nebraska prison system is severely overcrowded and has been in a state of ongoing and varying degrees of crisis for the last several years. This system has triggered considerable focus and debate over all components of the criminal justice process, from appropriate penalties and the sorts of offenders entering the prison system to the conditions of the state’s overcrowded prisons to meaningful re-entry opportunities for those who leave prison.

This investigation looks at one component of the Nebraska prison system: women in state prison. Nationwide, the number of women in prison and jails is increasing. As the population of women in custody increases, the dynamic of accommodating this growing prison population is changing. This presents unique challenges for governments to house, rehabilitate, and transition women back to their communities. Women in the criminal justice system face different challenges than men and the population of female prisoners also have different needs which prison officials must accommodate.

Increasing incarceration rates for women has a more profound effect on others outside the prison walls. A high percentage of women who are locked up are mothers, and most of these women are the primary caretakers of minor children. These children are especially susceptible to the negative impacts and burdens of incarceration.

- Nebraska Correctional Center for Women (NCCW) is the sole secure facility for adult women in the Nebraska Department of Correctional Services (NDCS). NCCW has the current capacity of 275 beds but an average daily population of 345 prisoners. Like all other adult facilities in the NDCS, NCCW is currently housing more prisoners than capacity. NCCW is at 125.45% of design capacity as of June 2017.

- The number of women in prison has significantly increased in recent years. As of June 2017, about 422 women are in prison in Nebraska. Stated another way, that’s approximately 45 out of every 100,000 Nebraska women. Nebraska is slightly below the national average for state incarceration rates of women.

- In 2013, Nebraska had the fifth highest incarceration rate for girls with 119 out of every 100,000 girls in residential or committed placement.

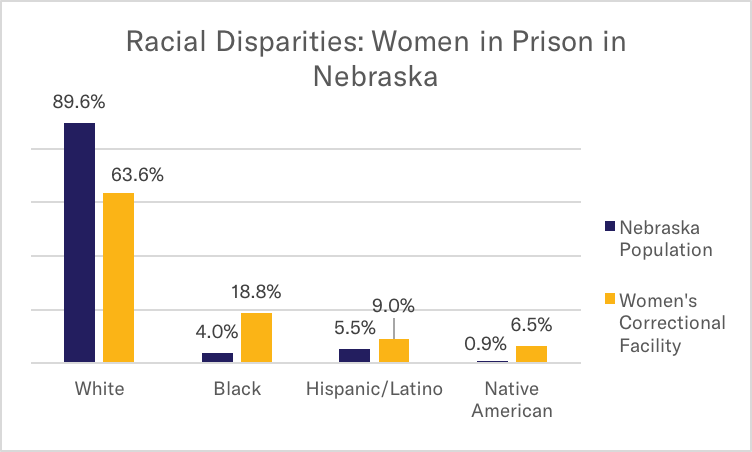

- The percentage of women of color in Nebraska’s prison is significantly over-representative of the percentage of women of color in the state. 86.1% of the population in Nebraska is white, 4.5% are Black or African-American and 9.2% Hispanic. In 2016, 18.8% of the Nebraska women prisoners were Black and 9% were Hispanic women. White women made up 63.6% of Nebraska’s female prisoner population.

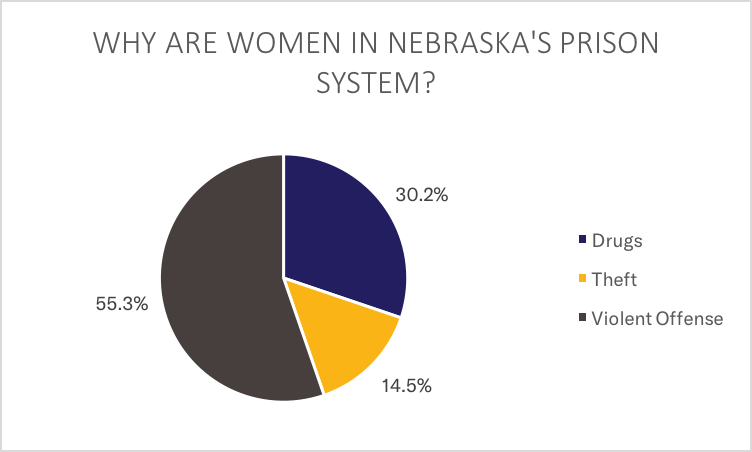

- In Nebraska, women offenders are in prison primarily for nonviolent crimes. Nearly half of women are in prison for drugs and theft. In 2014, 30.2% were serving sentences for drug offenses. 14.5% were serving time for theft.

- Nearly 41,000 Nebraska children, or about one in ten Nebraska kids, have had a parent in custody. Most of the children who have an incarcerated parent are 10 years of age or younger. No bordering states exceed this percentage, but Wyoming matches Nebraska.

- At least half of the women incarcerated in Nebraska prisons have a diagnosed mental illness, compared to about one fourth of Nebraska men who are incarcerated.

- In Nebraska, women who are incarcerated are routinely denied access to substance abuse treatment. For example, the most recent data from the NDCS indicates that about 10% of Nebraska women presently incarcerated at NCCW are on a wait list for substance abuse treatment. This is 32 of 345 women and includes pre- and post- parole eligibility. NCCW presently earns the dubious distinction of being tied for second place among Nebraska prison facilitates, with 15.9% of Nebraska women “jamming out” without access to meaningful programs and services prior to release.

- In Nebraska, the NDCS provides some menstrual pads to prisoners, but it does not provide tampons and panty-liner products free of charge to incarcerated women. Instead, Nebraska facilities routinely treat menstrual supplies as "luxury items" and women must purchase these supplies from the prison commissary in the same manner they purchase candy bars or chips.

- In Nebraska, there are presently no state statutes or regulations regarding the provision of abortion services for incarcerated women. Nebraska state officials do not track the number of pregnant prisoners who enter the prison system or become pregnant while serving sentences.

- The 2016 Prison Rape Elimination Act (PREA) Assessment report showed that 157 contacts were made about sexual assault or abuse in the prison system, which included crisis line calls. At NCCW, 13 investigations of sexual assaults or sexual harassment incidents were investigated. The majority, 12, of these were determined to be “unsubstantiated” or “unfounded”. Not a single report or investigation was referred to the local county attorney for prosecution, regarding the NCCW or any other prison facility.

Women prisoners generally serve their sentences in the Nebraska Correctional Center for Women (NCCW) in York, Nebraska. NCCW is the sole secure facility for adult women in the NDCS. NCCW has the current capacity of 275 beds but an average daily population of 345 prisoners. Like all other adult facilities in the NDCS, NCCW is currently housing more prisoners than capacity. NCCW is at 125.45% of design capacity as of June 2017[1].

Unlike the prisons dedicated to housing men, NCCW has its own on-site “diagnostic and evaluation” center for all newly arriving prisoners. The diagnostic and evaluation process is a standard assessment for all prisoners in which they take part in an orientation process prior to placement in general population. The prisoners are supposed to be evaluated for medical and mental health needs and personalized plans are to be developed to assist in creating their individualized rehabilitative programming.

York is a small city of less than 8,000 residents.[2] The majority of women who are sentenced to prison and housed in York are from Omaha or Lincoln. Both of these cities are a considerable distance from York. Omaha is a nearly two hour drive, one way[3], Lincoln is one hour away.[4] Very few of the prisoners in NCCW are from York, which means that the vast majority of the prisoners in York are at least an hour from their families. This adds a significant and confounding dimension to separation that prisoners, and their families, experience. This geographic challenge makes it much more difficult for women prisoners to maintain meaningful family and community connections, particularly with younger children.

Some women prisoners can serve their sentences at one of the two minimum security facilities, the Community Corrections Center in Lincoln (CCC-L) and the Community Corrections Center in Omaha (CCC-O). Both facilities are community residential programs, commonly referred to as work release centers, as many of the prisoners housed in these facilities work in the community. CCC-O can house 156 male prisoners and 24 female prisoners. CCC-L can house 312 male prisoners and 88 female prisoners. CCC-L was at 189.50% of design capacity as of June 2017; CCC-O was at 181.11% of design capacity.[5]

The NDCS completed construction of a 100-bed structure at CCC-L to house mostly low-level, community offenders. A second phase of construction provides for a 160-bed "community transitional housing" unit for female prisoners, which is set for completion in March 2019.[6]

Across the country, the population of women in prisons and jails is increasing. The number of women in federal prison has significantly increased. “Since 1980, the female prison population in America has grown by 716%.” The increase in population is not limited to federal prisons, but is also growing at the local jail and state prison level. Since 2010, the female jail population has consistently been the fastest growing correctional population.[7]

The explanation for the increase in women being jailed and imprisoned can be traced to the “war on drugs”, or aggressive law enforcement response to drugs, including drug possession. “Broken windows” policing, or law enforcement responses to quality of life and low-level offenses, is seen as a way of preventing more serious crimes. The focus on minor offenses and simple drug possession resulted in increased risk of arrest for both men and women. But this practice led to significantly more arrests of women. This is because women are more likely to be involved in the targeted minor offenses, such as simple drug possession, or the type of activity targeted by both drug enforcement and broken windows policing.[8]

In Nebraska, the number of women in prison has significantly increased in recent years. As of June 2017, about 422 women are in prison in Nebraska. Stated another way, that’s approximately 45 out of every 100,000 Nebraska women. Nebraska is slightly below the national average for state incarceration rates of women.[9] However, Nebraska had the fifth highest incarceration rate for girls in 2013 with 119 out of every 100,000 girls in residential or committed placement.[10]

Across the country, low-income women and women of color are disproportionately represented in incarcerated populations. Nationwide data indicate that approximately two-thirds of women in jail are women of color.[11] National statistics for 2014 show that 44% were Black, 15% were Hispanic, and 36% were white.

The percentage of women of color in Nebraska’s prison is significantly over-representative of the percentage of women of color in the state. 89.6% of the population in Nebraska is white, 4% are Black or African-American, 5.5% Hispanic and 0.9% were Native American.[12] In 2016, 18.8% of the Nebraska women prisoners were Black, 9% were Hispanic women and 6.5% were Native American. White women made up 63.6% of the Nebraska female prisoner population.[13]

Across the country, women are generally incarcerated for crimes related to substance abuse and property crimes.[14] The increase in women becoming involved in the criminal justice system can be traced to changes in state and federal drug policies that included prosecution of both users and distributors.[15] Law enforcement practices of targeting users and low-level drug offenders led to an increase in women being charged with drug offenses.

Women are more likely than men to be incarcerated for committing property crimes, such as theft or fraud.[16] Female prisoners are much less likely than male prisoners to have committed violent crimes. Of note, those women who have been convicted of violent or assaultive crimes more often committed such crimes in self-defense, such as in situations of intimate partner violence, than in calculated or premeditated manners. The overwhelming majority of violent offenses committed by women were against family members or intimates in a domestic relationship.[17]

In Nebraska, women offenders are in prison primarily for nonviolent crimes. Nearly half of women prisoners are in custody for drugs or theft. In 2014, 30.2% of women in prison were serving sentences for drug offenses. 14.5% were serving time for theft. The most violent category of offenses make up a much smaller share among women prisoners: homicide sentences only represent 6.6% of the female prisoner population and those women serving time for sex offenses is 2.5%.[18]

Across the country, approximately seven in ten women under correctional sanction have minor children.[19] Most are single mothers. Women prisoners face significant obstacles in maintaining relationships with their children. Many of the women in prison leave children at home. The separation from children is something that male prisoners experience as well, but this problem is often more complex with women as they are more likely to have been the primary, or even sole, parent for young children at the time they were sentenced. Given the compounding effects of separation, reentry into children’s lives is difficult for female prisoners as well as their children.

Nearly 41,000 Nebraska children, or about one in ten Nebraska kids, have had a parent in custody. Most of the children who have an incarcerated parent are 10 years of age or younger. No bordering states exceed this percentage, but Wyoming matches Nebraska.[20]

NDCS began a Parenting Program for women prisoners in 1974. It was one of the first programs in the United States to be introduced in a women’s correctional facility. In 1994, the Parenting Program was expanded to include an on-grounds nursery for children born to eligible women prisoners while they were incarcerated. This is a 15-bed unit. The maximum participation period for the Parenting Program is generally 18 months. The overall goal of the program is to improve parenting skills and create a positive and nurturing bond between mother and baby.

Extensive visitation with children is allowed and includes overnight on-grounds visits and extended day visits. Children between the ages of 1 and 6 may spend up to five nights per month with their mothers in a living unit separated from general population. Newborns and children up to the age of 16 may have extended on-grounds day visits in the parenting program area.

Across the country, women in prisons receive substandard health care and insufficient mental health services. Women who are incarcerated have disproportionately higher rates of health problems. One sample of 154 incarcerated women showed that 95% of them reported a minimum of one physical symptom of poor health. [21] A more recent study shows that 67% of women in jails and 63% of women in prisons report chronic health conditions.[22]

There are several explanations as to why incarcerated women have more healthcare needs. Many women who are incarcerated did not have access to health care services prior to their prison sentences. This is a common characteristic among people of low socioeconomic status and many who are incarcerated come from such a background. Women in prison suffer higher rates of substance abuse and often lack good nutrition, which further contributes to a likelihood of poor health. Additionally, a disproportionate number of women have been victims of sexual and physical abuse prior to incarceration and have a higher frequency of STDs and illnesses relating to STDs.[23]

Nebraska’s severely overcrowded and under-resourced prisons result in women prisoners frequently being denied adequate health care including medical, mental, dental, and reproductive health care and access to programming and services. The allegations contained in a recent federal lawsuit filed on behalf of prisoners offers insight into the shortcomings of the health care services for women in Nebraska’s prisons.[24]

Zoe Rena, incarcerated in York, repeatedly requested treatment for tooth, mouth, and jaw pain, but staff withheld or delayed treatment, causing her more pain and discomfort. On two occasions, medical staff noted she had abscesses in her mouth following an earlier procedure, but did nothing to treat them. Ms. Rena did not have any dental care until two full months after the abscesses were first noted, and did not receive appropriate treatment for her condition. She had a tooth pulled even though it was only chipped and could have been saved. On another occasion, Ms. Rena went to the dentist for what she thought was a root canal, only to have more teeth pulled. She is afraid to go back to the dentist because she thinks the dentist will just pull more of her teeth. Ms. Rena suffered from other health problems that were also mistreated. She experienced a menstrual cycle that lasted for three consecutive months; she was given an ultrasound of her ovaries and uterus, but was never told the results and was never informed of a treatment plan. Additionally, Ms. Rena experienced a chronic skin rash that causes significant discomfort. The rash did not occur before she was incarcerated, and staff have been unable to diagnose and properly treat this condition. Staff will not send her to a dermatologist for treatment.

Mental Health

Across the country, a significant number, over two-thirds, of incarcerated women have a history of mental health problems.[25] Sixty-six percent of women in prison reported a history of a mental disorder. This is almost twice the rate of men in prison. One in five women in prison had recently experienced what could be considered serious psychological distress, compared to one in seven men in prison.

At least half of the women incarcerated in Nebraska prisons have a diagnosed mental illness, compared to about one fourth of Nebraska men who are incarcerated.[26] As is the case with general health care, the effects of overcrowding can be felt with the shortage of mental health treatment for women in Nebraska’s prisons.

Staff vacancies are a persistent feature in Nebraska’s prison system. There are vacancies throughout NDCS, from frontline workers to behavioral health staff. Staff shortages exist at all facilities including NCCW. As of June 2017, NCCW had five vacancies for positions working to address women prisoners’ behavioral health concerns. These vacancies include three Mental Health Practitioner II positions and two Chemical Dependency Counselors.[27] While these vacancies exist at other facilities, they are more profound at NCCW for two reasons. First, there are fewer prisoners at NCCW (345 as of June 2017) compared to male facilities. For instance, the Nebraska State Penitentiary has 1,343 prisoners as of June 2017, but has eight behavioral health staff vacancies. The absence of five behavioral health staff is likely a significant portion of the total behavioral health staff at NCCW.

The second reason that mental health staff vacancies have a greater impact on NCCW prisoners is that women prisoners are much more likely to have a history of substance abuse and/or mental health problems, which often contribute to their reasons for being incarcerated. The women prisoner population is in dire need of mental health and substance abuse treatment.

The same lawsuit referenced above provides perspective on the consequences of inadequate mental health treatment for women in prison.[28] Hannah Sabata is a 24-year-old female prisoner incarcerated in the NCCW. Ms. Sabata has schizophrenia and is living with HIV. Throughout her time in prison, she has experienced lapses and delays in receiving prescription medications for her HIV. This exacerbates her disabilities and places her at increased risk of harm. She has been housed in isolation several times at NCCW, frequently because of her schizophrenia. Ms. Sabata’s stays in isolation regularly last more than one month. In total, she has spent more than two years in isolation, which has exacerbated her psychiatric disability and increased her suicidal ideations.

Angelic Norris, another woman incarcerated in the NCCW, is legally blind. She is also diagnosed with a developmental disability and bipolar disorder. Ms. Norris suffers from hypertension for which she is not receiving adequate treatment, putting her at increased risk of further harm. She has been housed in isolation intermittently for her entire time at NCCW. Ms. Norris has frequently been housed in isolation because of her intellectual and psychiatric disabilities and as punishment for behaviors related to her blindness. She has also routinely been placed in isolation for threatening self-harm. Ms. Norris cannot fill out her own grievance forms due to her blindness and prison staff fail to assist her. She has been provided with talking clocks, Braille blocks, and walking canes by the Commission for the Blind, but these accommodations have been routinely confiscated by staff.

Substance Abuse Treatment

Across the country, women in prison are significantly more likely than incarcerated men to have severe substance abuse histories, co-occurring mental disorders, and high rates of past treatment for both. Approximately 50% of female offenders are likely to have histories of physical or sexual abuse, and women are more likely than men to be victims of domestic violence. Past or current victimization can contribute to drug or alcohol abuse, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and criminal activity.[29]

In Nebraska, women who are incarcerated are routinely denied access to substance abuse treatment. For example, the most recent data from the NDCS indicates that about 10%, or 32 of 345, of Nebraska women presently incarcerated pre- and post- parole eligibility at NCCW are on a wait list for substance abuse treatment. NCCW presently earns the dubious distinction of being tied for second place among Nebraska prison facilitates, with 15.9% of Nebraska women “jamming out” without access to meaningful programs and services prior to release. This lack of access to basic behavioral health care impacts the quality of life for those incarcerated, affects their ability to access the parole process, and limits their chances of successful re-entry to our communities.[30]

Menstrual Products

Women have specific health needs that differ from those of men. This reality does not change when women are incarcerated. Throughout the country, jails and prison often fail to accommodate the most basic and personal hygienic needs of female prisoners.

Nationally, on August 1, 2017, the U.S. Bureau of Prisons issued an operations memorandum amending its regulations to require that women prisoners have more access to free tampons and pads.[31] Specifically, the memorandum requires all wardens of federal facilities or units housing female prisoners to provide tampons, regular and super-size; Maxi Pads with wings, regular and super-size; and panty liners, regular. These items are to be provided at no cost to the prisoners. The change in regulation, which broadened an existing policy, was created in response to a bill introduced in the United States Senate by Senators Cory Booker and Elizabeth Warren which would have made a similar requirement in statute.

In Nebraska, the NDCS provides some menstrual pads to prisoners, but it does not provide tampons and panty liners free of charge to incarcerated women. Instead, Nebraska facilities routinely treat menstrual supplies as "luxury items" and women must purchase these supplies from the prison commissary in the same manner they may purchase candy bars or chips. At NCCW, a package of 10 tampons costs $2.04 or $2.34, depending on the size. Panty liners cost $1.22 or $1.33. In many cases, these prices are significantly higher than what one would pay at their local grocery or drug store. Prisoners are advised that prices in the canteen are subject to change “without notice”.[32] If a prisoner cannot or does not order items from the canteen, she cannot obtain these items from another source, including other prisoners or outside donations by friends, families, or community groups.

Reproductive Health

Being in prison does limit many freedoms, but it does not restrict all rights. Included in the rights that are retained while a woman is in prison, is the right to decide whether to continue a pregnancy. Courts, including the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals that includes Nebraska, have consistently held that women retain the right to have an abortion if they are incarcerated. [33] Nationwide, it is estimated that 6 to 10% of women who enter prison or jail are pregnant.[34]

In Nebraska, there are presently no state statutes or regulations regarding the provision of abortion services for incarcerated women. Nebraska state officials do not track the number of pregnant prisoners who enter the prison system or become pregnant while serving sentences.

Sexual Assault

Many incarcerated women were sexually assaulted or suffered similar trauma prior to their entry into the prison system. 80% of women in U.S. prisons suffered severe violence as girls, and 75% were abused by an intimate partner when they were adults.[35] A more recent study indicates that this number is likely higher. In August 2016, the Vera Institute of Justice found that 86% of women in jail report having experienced sexual violence in their lifetime.[36]

Spending time in custody can be traumatizing for all, but it can be particularly traumatizing for women survivors of domestic or sexual assault. Many standard correctional procedures can be a trigger for painful or repressed memories and can result in emotional symptoms of depression or Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). Routine searches, the use of restraints, and the non-private nature of life in prison can cause victims to re-experience personal trauma. Doing typically private things, such as dressing, showering, or using the restroom in a public, monitored environment can trigger trauma for sexual assault or abuse survivors. Typical reactions that a trauma survivor might have to such stressors, including withdrawal or anger, may result in disciplinary sanctions being imposed. These sanctions can include solitary confinement or similar isolation which can further traumatize these prisoners. As stated above, counseling and support for sexual assault survivors is lacking in many prisons and jails.

In addition to the trauma that former sexual assault victims experience with prison life, some prisoners experience sexual assault while in prison. To address the nationwide problem of sexual assault in prison, Congress passed the Prison Rape Elimination Act (PREA) in 2003. The goals of the PREA are to eliminate sexual abuse in confinement. The law applies to federal and state prisons and local jails. Correctional facilities are to screen all arrestees/detainees to determine risk of sexual abuse at intake and to respond appropriately to sexual assault incidents within the facilities. Each facility is to have a written policy or procedure which must be approved by the U.S. Department of Justice.

When Congress passed the PREA, it required states to certify that they would comply with the standards set by the Department of Justice (DOJ). A handful of states, including Nebraska, could not initially certify that they would comply with the standards in 2014.[37]

On March 31, 2016, Nebraska Governor Pete Ricketts issued an assurance to the DOJ that Nebraska will use at least 5% of any grants to achieve full compliance with the PREA. Nebraska is one of 42 jurisdictions that issued similar assurances in 2016. 10 states issued certifications that they were compliant with the PREA. Two states, Arkansas and Utah, have opted out of PREA compliance efforts.

The PREA contains a number of standards for prisons and jails to meet. The standards generally address issues relating to the prevention, detection and response to sexual assault of prisoners. Towards the ostensible goal to become compliant with the PREA, NDCS issues an annual assessment reporting numbers of complaints or investigations and the outcome of those investigations. NDCS states that it “has a zero tolerance policy” regarding sexual assault, sexual abuse, or sexual harassment of prisoners or staff.

In 2016, NDCS partnered with the Nebraska Coalition to End Sexual and Domestic Violence to provide prisoners with a resource to report or discuss incidents of sexual assault or abuse. The 2016 PREA Assessment report showed that 157 contacts were made, which included crisis line calls. At NCCW, 13 investigations of sexual assaults or sexual harassment incidents were conducted. The majority, 12, of these were determined to be “unsubstantiated” or “unfounded”. Not a single report or investigation from any Nebraska prison facility, including the NCCW, was referred to the local county attorney for prosecution. This includes the other facilities that house women, CCC-L and CCC-O, which also had no referrals for prosecution.

1) Alternatives to arrest and incarceration

One way to prevent women from ending up in prison is through reform in police practices, including changing which offenses result in arrests. Prioritizing policing on lower-level offenses, particularly drug offenses, has contributed to the increase in women in the criminal justice system. A greater focus on minor offenses increases the likelihood that women will be arrested and jailed. Even a few days in jail increases the probability that an offender will end up serving more time in custody. Law enforcement and prosecutors should implement options and alternatives to jailing offenders. Some communities have diversion programs that are designed to treat those who are suffering from trauma, substance use, or mental health deterioration through alternatives to jailing them. These programs often work with a public mental health system or similar entity trained to address mental health crisis situations.[38]

Crisis intervention team programs can be beneficial for diverting women from prison, given the high percentage of female offenders who live with a mental illness.[39] In recent years, the Omaha Police Department has been working with the Douglas County Crisis Response Team, a 24/7 program that provides therapists and assistance to law enforcement should they respond to a call involving someone who is mentally ill. Of the 1,193 behavioral health forms, or referrals to the Crisis Response Team for 2014-15, only 1.8% resulted in arrest while the large majority were referred or transported to a treatment facility.[40] Ultimately, the decision to contact the Crisis Response Team is up to the responding officers. Continued training and education will ensure that this program is effectively used. This is a good model worthy of exploration by other communities.

Reforms to Nebraska’s debtors’ prison should be implemented with all deliberate speed. Nebraska recently enacted bond reform to avoid unnecessary pretrial detention by requiring courts to consider an individual’s financial ability to post a money bond and broadened the authority of courts to release defendants under supervision. [41]

One significant, yet simple, reform to the problems women face in prison would be to avoid sending women to prison. As in other Smart Justice reforms, policymakers should invest in meaningful alternatives to prison such as drug courts, veterans’ court, mental health courts, and similar problem-solving focused courts.

2) Improve access to meaningful programming and services in prison to improve quality of life and support successful re-entry

Proper programming and services in prisons are vital to the successful reentry of female prisoners. Access to basic health care including mental, physical, dental and behavioral health services must be provided in the same manner as the community standard of care under Nebraska state law.[42] Drug treatment is critically important for female prisoners because they are significantly more likely to have a drug problem, a mental health diagnosis, or some similar dual diagnosis.

3) Improve Access to Supportive Services for Trauma Survivors

Nebraska should explore toll free hotlines and other practices to address gaps in the provision of services for trauma survivors who are incarcerated.[43]

4) Provide meaningful contact with children

Nebraska should maintain and broaden programs that encourage and facilitate meaningful, healthy relationships with mothers and children.

Across the country, some jails have developed parenting classes and parental support to help mothers prepare for reunification. For instance, in San Francisco, a nonprofit entity provides services directly in the jail such as parental education, therapeutic visitation, contact visitation and assistance in reentry and reunification upon release.[44]

To maintain regular contact between parent and child, policies that provide for meaningful visitation should be implemented. Some jails across the country allow for regular, such as weekly, contact visits between prisoner-parents and their children. Allegheny County, Pennsylvania operates the Family Support Program, which similarly accommodates contact visits between prisoner, usually women, and their children.[45]

One way to reduce barriers to contact with children short of providing for contact visits is to lower the costs of telephone calls from jails. While the costs of phone calls from the state prisons are not cost-prohibitive, the costs at the county level for jails can be very costly.

5) Provide free feminine hygiene products for women prisoners, following the federal lead.

A simple reform for women’s health would be for policymakers to emulate the federal Bureau of Prisons and provide free feminine hygiene products. [46] This could be done by administrative directive, or it could be accommodated by legislative action by state senators.

Nebraska prisons’ rules and regulations should be updated to ensure clarity in respecting a woman’s right to terminate a pregnancy while incarcerated.

A comprehensive reproductive justice framework is needed to address a plethora of issues. Pregnant women should not be subjected to solitary confinement. Anti-shackling laws for pregnant prisoners during pregnancy, birth, and post-partum are needed. An examination on existing prenatal care standards including accommodations for clothing, nutrition, care, labor and delivery is necessary. An examination of rules and regulations to ensure breastfeeding and lactation support should also be made a priority.

In consideration of extreme overcrowding throughout Nebraska’s prisons, pending litigation, and other factors, prison reform will remain a top agenda item for Nebraska leaders. As such, the time is ripe for policymakers in Nebraska to conduct further review and analysis of the needs of women in our prisons. Leaders should explore the above policy reform solutions to ensure the unique needs of incarcerated women are being addressed in compliance with best practices in law and policy.

[1] NDCS Quarterly Data Sheet, June 2017

[5] NDCS Quarterly Data Sheet, June 2017

[7] Correctional Populations in the United States, 2013-Bureau of Justice Statistics-published December 29, 2014.

[8] Vera Institute for Justice, “Overlooked: Women and Jails in an Era of Reform” August 2016.

[10] NDCS Quarterly Data Sheet, April-June 2017] Sickmund, M., Sladky, M. Kang, T.J., and Puzzanchera, C. (2015). Easy Access to the Census of Juveniles in Residential Placement. Washington, D.C.: Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention.

[11] Lawrence A. Greenfeld and Tracy L. Snell, Women Offenders U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics 2014

[13]2016 Annual PREA Assessment, Nebraska Department of Correctional Services Report

[19] Susan W. McCampbell, “The Gender-Responsive Strategies Project: Jail Applications” U.S. Department of Justice, National Institute of Corrections, 2005

[20] “A Shared Sentence” Kids Count, April 2016 Policy Report

[21] Young, D. “Health Status and Service Use Among Incarcerated Women” Family and Community Health 1998; 21(3):16-31.

[22] Maruschak, LM. Medical problems of state and federal prisoners and jail inmates, 2011-12. Washington: Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2015.

[23] Fearn NE, Parker K. Health care for women inmates: Issues, perceptions, and policy considerations. California Journal of Health Promotion 2005; 3(2):1-22.

[24] Sabata v. Nebraska Department of Correctional Services, 4:17-cv-03107 (Dist. Ct. Neb.), filed August 15, 2017.

[25] US Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, “Indicators of Mental Health Problems Reported by Prisoners and Jail Inmates 2011-12” June 2017”, Jennifer Bronson and Marcus Berzofsky

[27] NDCS Quarterly Data Sheet, June 2017.

[28] Sabata v. Nebraska Department of Correctional Services, 4:17-cv-03107 (Dist. Ct. Neb.), filed August 15, 2017.