Let Down and Locked Up: Nebraska Women in Prison

Introduction | Key Findings | Nebraska Women’s Prisons | The Number of Women in Prison Is on the Rise | Women of Color are Overrepresented | Unique Pathways to Prison | Parenting in Prison | Health Care for Incarcerated Women | Recommendations for Reform | Conclusion

The ACLU of Nebraska is a non-profit, non-partisan organization that works to defend and strengthen the individual rights and liberties guaranteed in the United States and Nebraska Constitutions through policy advocacy, litigation and education. For over fifty years, the ACLU of Nebraska has been a constant guardian for freedom and liberty fighting for the civil rights and civil liberties of all Nebraskans. The ACLU of Nebraska intentionally prioritizes the needs of historically unrepresented and underrepresented groups and individuals who have been denied their rights; including people of color, women, LGBT Nebraskans, persons incarcerated and formerly incarcerated, students, and people with disabilities.

Introduction

Nebraska's criminal justice policies have created a system of mass incarceration. This hurts our communities and disproportionately impacts low income families and people of color. Existing conditions violate the Eighth Amendment's protection against cruel and unusual punishment and do not provide for meaningful transition back into our communities and our economy. The ACLU is leading the way to rethink and reform these policies and conditions though our campaign for Smart Justice to protect individual rights, reduce the taxpayer burden, and make our communities safer.

Existing "tough on crime" policies, particularly around punitive drug policies, have failed to achieve public safety while putting an unprecedented number of people behind bars and eroding constitutional rights. This system also erodes economic opportunity, family stability, and civic engagement during and after incarceration. In many instances, a criminal record becomes a life-long barrier to accessing basic human needs and ensuring individual and family stability.

The Nebraska prison system is severely overcrowded and has been in a state of ongoing and varying degrees of crisis for the last several years. This system has triggered considerable focus and debate over all components of the criminal justice process, from appropriate penalties and the sorts of offenders entering the prison system to the conditions of the state’s overcrowded prisons to meaningful re-entry opportunities for those who leave prison.

This investigation looks at one component of the Nebraska prison system: women in state prison. Nationwide, the number of women in prison and jails is increasing. As the population of women in custody increases, the dynamic of accommodating this growing prison population is changing. This presents unique challenges for governments to house, rehabilitate, and transition women back to their communities. Women in the criminal justice system face different challenges than men and the population of female prisoners also have different needs which prison officials must accommodate.

Increasing incarceration rates for women has a more profound effect on others outside the prison walls. A high percentage of women who are locked up are mothers, and most of these women are the primary caretakers of minor children. These children are especially susceptible to the negative impacts and burdens of incarceration.

Key Findings

- Nebraska Correctional Center for Women (NCCW) is the sole secure facility for adult women in the Nebraska Department of Correctional Services (NDCS). NCCW has the current capacity of 275 beds but an average daily population of 345 prisoners. Like all other adult facilities in the NDCS, NCCW is currently housing more prisoners than capacity. NCCW is at 125.45% of design capacity as of June 2017.

- The number of women in prison has significantly increased in recent years. As of June 2017, about 422 women are in prison in Nebraska. Stated another way, that’s approximately 45 out of every 100,000 Nebraska women. Nebraska is slightly below the national average for state incarceration rates of women.

- In 2013, Nebraska had the fifth highest incarceration rate for girls with 119 out of every 100,000 girls in residential or committed placement.

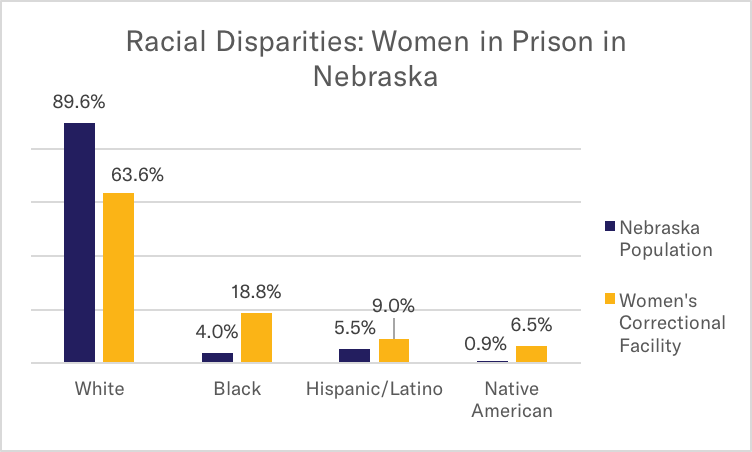

- The percentage of women of color in Nebraska’s prison is significantly over-representative of the percentage of women of color in the state. 86.1% of the population in Nebraska is white, 4.5% are Black or African-American and 9.2% Hispanic. In 2016, 18.8% of the Nebraska women prisoners were Black and 9% were Hispanic women. White women made up 63.6% of Nebraska’s female prisoner population.

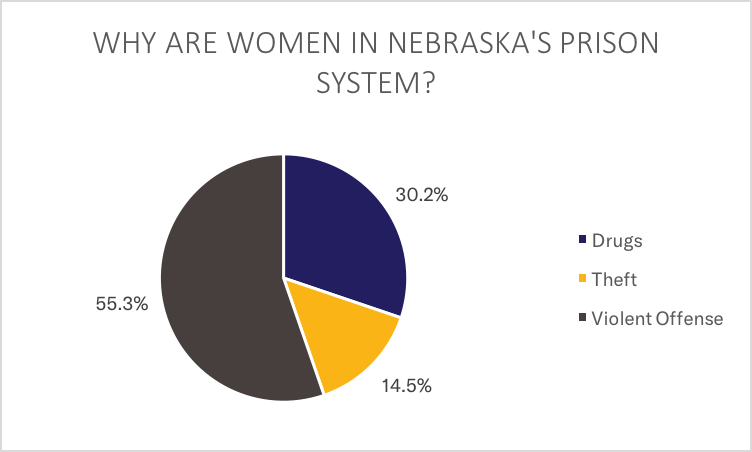

- In Nebraska, women offenders are in prison primarily for nonviolent crimes. Nearly half of women are in prison for drugs and theft. In 2014, 30.2% were serving sentences for drug offenses. 14.5% were serving time for theft.

- Nearly 41,000 Nebraska children, or about one in ten Nebraska kids, have had a parent in custody. Most of the children who have an incarcerated parent are 10 years of age or younger. No bordering states exceed this percentage, but Wyoming matches Nebraska.

- At least half of the women incarcerated in Nebraska prisons have a diagnosed mental illness, compared to about one fourth of Nebraska men who are incarcerated.

- In Nebraska, women who are incarcerated are routinely denied access to substance abuse treatment. For example, the most recent data from the NDCS indicates that about 10% of Nebraska women presently incarcerated at NCCW are on a wait list for substance abuse treatment. This is 32 of 345 women and includes pre- and post- parole eligibility. NCCW presently earns the dubious distinction of being tied for second place among Nebraska prison facilitates, with 15.9% of Nebraska women “jamming out” without access to meaningful programs and services prior to release.

- In Nebraska, the NDCS provides some menstrual pads to prisoners, but it does not provide tampons and panty-liner products free of charge to incarcerated women. Instead, Nebraska facilities routinely treat menstrual supplies as "luxury items" and women must purchase these supplies from the prison commissary in the same manner they purchase candy bars or chips.

- In Nebraska, there are presently no state statutes or regulations regarding the provision of abortion services for incarcerated women. Nebraska state officials do not track the number of pregnant prisoners who enter the prison system or become pregnant while serving sentences.

- The 2016 Prison Rape Elimination Act (PREA) Assessment report showed that 157 contacts were made about sexual assault or abuse in the prison system, which included crisis line calls. At NCCW, 13 investigations of sexual assaults or sexual harassment incidents were investigated. The majority, 12, of these were determined to be “unsubstantiated” or “unfounded”. Not a single report or investigation was referred to the local county attorney for prosecution, regarding the NCCW or any other prison facility.

Nebraska Women’s Prisons

Women prisoners generally serve their sentences in the Nebraska Correctional Center for Women (NCCW) in York, Nebraska. NCCW is the sole secure facility for adult women in the NDCS. NCCW has the current capacity of 275 beds but an average daily population of 345 prisoners. Like all other adult facilities in the NDCS, NCCW is currently housing more prisoners than capacity. NCCW is at 125.45% of design capacity as of June 2017[1].

Unlike the prisons dedicated to housing men, NCCW has its own on-site “diagnostic and evaluation” center for all newly arriving prisoners. The diagnostic and evaluation process is a standard assessment for all prisoners in which they take part in an orientation process prior to placement in general population. The prisoners are supposed to be evaluated for medical and mental health needs and personalized plans are to be developed to assist in creating their individualized rehabilitative programming.

York is a small city of less than 8,000 residents.[2] The majority of women who are sentenced to prison and housed in York are from Omaha or Lincoln. Both of these cities are a considerable distance from York. Omaha is a nearly two hour drive, one way[3], Lincoln is one hour away.[4] Very few of the prisoners in NCCW are from York, which means that the vast majority of the prisoners in York are at least an hour from their families. This adds a significant and confounding dimension to separation that prisoners, and their families, experience. This geographic challenge makes it much more difficult for women prisoners to maintain meaningful family and community connections, particularly with younger children.

Some women prisoners can serve their sentences at one of the two minimum security facilities, the Community Corrections Center in Lincoln (CCC-L) and the Community Corrections Center in Omaha (CCC-O). Both facilities are community residential programs, commonly referred to as work release centers, as many of the prisoners housed in these facilities work in the community. CCC-O can house 156 male prisoners and 24 female prisoners. CCC-L can house 312 male prisoners and 88 female prisoners. CCC-L was at 189.50% of design capacity as of June 2017; CCC-O was at 181.11% of design capacity.[5]

The NDCS completed construction of a 100-bed structure at CCC-L to house mostly low-level, community offenders. A second phase of construction provides for a 160-bed "community transitional housing" unit for female prisoners, which is set for completion in March 2019.[6]

The Number of Women in Prison is on the Rise

Across the country, the population of women in prisons and jails is increasing. The number of women in federal prison has significantly increased. “Since 1980, the female prison population in America has grown by 716%.” The increase in population is not limited to federal prisons, but is also growing at the local jail and state prison level. Since 2010, the female jail population has consistently been the fastest growing correctional population.[7]

The explanation for the increase in women being jailed and imprisoned can be traced to the “war on drugs”, or aggressive law enforcement response to drugs, including drug possession. “Broken windows” policing, or law enforcement responses to quality of life and low-level offenses, is seen as a way of preventing more serious crimes. The focus on minor offenses and simple drug possession resulted in increased risk of arrest for both men and women. But this practice led to significantly more arrests of women. This is because women are more likely to be involved in the targeted minor offenses, such as simple drug possession, or the type of activity targeted by both drug enforcement and broken windows policing.[8]

In Nebraska, the number of women in prison has significantly increased in recent years. As of June 2017, about 422 women are in prison in Nebraska. Stated another way, that’s approximately 45 out of every 100,000 Nebraska women. Nebraska is slightly below the national average for state incarceration rates of women.[9] However, Nebraska had the fifth highest incarceration rate for girls in 2013 with 119 out of every 100,000 girls in residential or committed placement.[10]

Women of Color are Overrepresented

Across the country, low-income women and women of color are disproportionately represented in incarcerated populations. Nationwide data indicate that approximately two-thirds of women in jail are women of color.[11] National statistics for 2014 show that 44% were Black, 15% were Hispanic, and 36% were white.

The percentage of women of color in Nebraska’s prison is significantly over-representative of the percentage of women of color in the state. 89.6% of the population in Nebraska is white, 4% are Black or African-American, 5.5% Hispanic and 0.9% were Native American.[12] In 2016, 18.8% of the Nebraska women prisoners were Black, 9% were Hispanic women and 6.5% were Native American. White women made up 63.6% of the Nebraska female prisoner population.[13]

Unique Pathways to Prison

Across the country, women are generally incarcerated for crimes related to substance abuse and property crimes.[14] The increase in women becoming involved in the criminal justice system can be traced to changes in state and federal drug policies that included prosecution of both users and distributors.[15] Law enforcement practices of targeting users and low-level drug offenders led to an increase in women being charged with drug offenses.

Women are more likely than men to be incarcerated for committing property crimes, such as theft or fraud.[16] Female prisoners are much less likely than male prisoners to have committed violent crimes. Of note, those women who have been convicted of violent or assaultive crimes more often committed such crimes in self-defense, such as in situations of intimate partner violence, than in calculated or premeditated manners. The overwhelming majority of violent offenses committed by women were against family members or intimates in a domestic relationship.[17]

In Nebraska, women offenders are in prison primarily for nonviolent crimes. Nearly half of women prisoners are in custody for drugs or theft. In 2014, 30.2% of women in prison were serving sentences for drug offenses. 14.5% were serving time for theft. The most violent category of offenses make up a much smaller share among women prisoners: homicide sentences only represent 6.6% of the female prisoner population and those women serving time for sex offenses is 2.5%.[18]

Parenting in Prison

Across the country, approximately seven in ten women under correctional sanction have minor children.[19] Most are single mothers. Women prisoners face significant obstacles in maintaining relationships with their children. Many of the women in prison leave children at home. The separation from children is something that male prisoners experience as well, but this problem is often more complex with women as they are more likely to have been the primary, or even sole, parent for young children at the time they were sentenced. Given the compounding effects of separation, reentry into children’s lives is difficult for female prisoners as well as their children.

Nearly 41,000 Nebraska children, or about one in ten Nebraska kids, have had a parent in custody. Most of the children who have an incarcerated parent are 10 years of age or younger. No bordering states exceed this percentage, but Wyoming matches Nebraska.[20]

NDCS began a Parenting Program for women prisoners in 1974. It was one of the first programs in the United States to be introduced in a women’s correctional facility. In 1994, the Parenting Program was expanded to include an on-grounds nursery for children born to eligible women prisoners while they were incarcerated. This is a 15-bed unit. The maximum participation period for the Parenting Program is generally 18 months. The overall goal of the program is to improve parenting skills and create a positive and nurturing bond between mother and baby.

Extensive visitation with children is allowed and includes overnight on-grounds visits and extended day visits. Children between the ages of 1 and 6 may spend up to five nights per month with their mothers in a living unit separated from general population. Newborns and children up to the age of 16 may have extended on-grounds day visits in the parenting program area.

Health Care for Incarcerated Women

Across the country, women in prisons receive substandard health care and insufficient mental health services. Women who are incarcerated have disproportionately higher rates of health problems. One sample of 154 incarcerated women showed that 95% of them reported a minimum of one physical symptom of poor health. [21] A more recent study shows that 67% of women in jails and 63% of women in prisons report chronic health conditions.[22]

There are several explanations as to why incarcerated women have more healthcare needs. Many women who are incarcerated did not have access to health care services prior to their prison sentences. This is a common characteristic among people of low socioeconomic status and many who are incarcerated come from such a background. Women in prison suffer higher rates of substance abuse and often lack good nutrition, which further contributes to a likelihood of poor health. Additionally, a disproportionate number of women have been victims of sexual and physical abuse prior to incarceration and have a higher frequency of STDs and illnesses relating to STDs.[23]

Nebraska’s severely overcrowded and under-resourced prisons result in women prisoners frequently being denied adequate health care including medical, mental, dental, and reproductive health care and access to programming and services. The allegations contained in a recent federal lawsuit filed on behalf of prisoners offers insight into the shortcomings of the health care services for women in Nebraska’s prisons.[24]

Zoe Rena, incarcerated in York, repeatedly requested treatment for tooth, mouth, and jaw pain, but staff withheld or delayed treatment, causing her more pain and discomfort. On two occasions, medical staff noted she had abscesses in her mouth following an earlier procedure, but did nothing to treat them. Ms. Rena did not have any dental care until two full months after the abscesses were first noted, and did not receive appropriate treatment for her condition. She had a tooth pulled even though it was only chipped and could have been saved. On another occasion, Ms. Rena went to the dentist for what she thought was a root canal, only to have more teeth pulled. She is afraid to go back to the dentist because she thinks the dentist will just pull more of her teeth. Ms. Rena suffered from other health problems that were also mistreated. She experienced a menstrual cycle that lasted for three consecutive months; she was given an ultrasound of her ovaries and uterus, but was never told the results and was never informed of a treatment plan. Additionally, Ms. Rena experienced a chronic skin rash that causes significant discomfort. The rash did not occur before she was incarcerated, and staff have been unable to diagnose and properly treat this condition. Staff will not send her to a dermatologist for treatment.

Mental Health

Across the country, a significant number, over two-thirds, of incarcerated women have a history of mental health problems.[25] Sixty-six percent of women in prison reported a history of a mental disorder. This is almost twice the rate of men in prison. One in five women in prison had recently experienced what could be considered serious psychological distress, compared to one in seven men in prison.

At least half of the women incarcerated in Nebraska prisons have a diagnosed mental illness, compared to about one fourth of Nebraska men who are incarcerated.[26] As is the case with general health care, the effects of overcrowding can be felt with the shortage of mental health treatment for women in Nebraska’s prisons.

Staff vacancies are a persistent feature in Nebraska’s prison system. There are vacancies throughout NDCS, from frontline workers to behavioral health staff. Staff shortages exist at all facilities including NCCW. As of June 2017, NCCW had five vacancies for positions working to address women prisoners’ behavioral health concerns. These vacancies include three Mental Health Practitioner II positions and two Chemical Dependency Counselors.[27] While these vacancies exist at other facilities, they are more profound at NCCW for two reasons. First, there are fewer prisoners at NCCW (345 as of June 2017) compared to male facilities. For instance, the Nebraska State Penitentiary has 1,343 prisoners as of June 2017, but has eight behavioral health staff vacancies. The absence of five behavioral health staff is likely a significant portion of the total behavioral health staff at NCCW.

The second reason that mental health staff vacancies have a greater impact on NCCW prisoners is that women prisoners are much more likely to have a history of substance abuse and/or mental health problems, which often contribute to their reasons for being incarcerated. The women prisoner population is in dire need of mental health and substance abuse treatment.

The same lawsuit referenced above provides perspective on the consequences of inadequate mental health treatment for women in prison.[28] Hannah Sabata is a 24-year-old female prisoner incarcerated in the NCCW. Ms. Sabata has schizophrenia and is living with HIV. Throughout her time in prison, she has experienced lapses and delays in receiving prescription medications for her HIV. This exacerbates her disabilities and places her at increased risk of harm. She has been housed in isolation several times at NCCW, frequently because of her schizophrenia. Ms. Sabata’s stays in isolation regularly last more than one month. In total, she has spent more than two years in isolation, which has exacerbated her psychiatric disability and increased her suicidal ideations.

Angelic Norris, another woman incarcerated in the NCCW, is legally blind. She is also diagnosed with a developmental disability and bipolar disorder. Ms. Norris suffers from hypertension for which she is not receiving adequate treatment, putting her at increased risk of further harm. She has been housed in isolation intermittently for her entire time at NCCW. Ms. Norris has frequently been housed in isolation because of her intellectual and psychiatric disabilities and as punishment for behaviors related to her blindness. She has also routinely been placed in isolation for threatening self-harm. Ms. Norris cannot fill out her own grievance forms due to her blindness and prison staff fail to assist her. She has been provided with talking clocks, Braille blocks, and walking canes by the Commission for the Blind, but these accommodations have been routinely confiscated by staff.

Substance Abuse Treatment

Across the country, women in prison are significantly more likely than incarcerated men to have severe substance abuse histories, co-occurring mental disorders, and high rates of past treatment for both. Approximately 50% of female offenders are likely to have histories of physical or sexual abuse, and women are more likely than men to be victims of domestic violence. Past or current victimization can contribute to drug or alcohol abuse, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and criminal activity.[29]

In Nebraska, women who are incarcerated are routinely denied access to substance abuse treatment. For example, the most recent data from the NDCS indicates that about 10%, or 32 of 345, of Nebraska women presently incarcerated pre- and post- parole eligibility at NCCW are on a wait list for substance abuse treatment. NCCW presently earns the dubious distinction of being tied for second place among Nebraska prison facilitates, with 15.9% of Nebraska women “jamming out” without access to meaningful programs and services prior to release. This lack of access to basic behavioral health care impacts the quality of life for those incarcerated, affects their ability to access the parole process, and limits their chances of successful re-entry to our communities.[30]

Menstrual Products

Women have specific health needs that differ from those of men. This reality does not change when women are incarcerated. Throughout the country, jails and prison often fail to accommodate the most basic and personal hygienic needs of female prisoners.

Nationally, on August 1, 2017, the U.S. Bureau of Prisons issued an operations memorandum amending its regulations to require that women prisoners have more access to free tampons and pads.[31] Specifically, the memorandum requires all wardens of federal facilities or units housing female prisoners to provide tampons, regular and super-size; Maxi Pads with wings, regular and super-size; and panty liners, regular. These items are to be provided at no cost to the prisoners. The change in regulation, which broadened an existing policy, was created in response to a bill introduced in the United States Senate by Senators Cory Booker and Elizabeth Warren which would have made a similar requirement in statute.

In Nebraska, the NDCS provides some menstrual pads to prisoners, but it does not provide tampons and panty liners free of charge to incarcerated women. Instead, Nebraska facilities routinely treat menstrual supplies as "luxury items" and women must purchase these supplies from the prison commissary in the same manner they may purchase candy bars or chips. At NCCW, a package of 10 tampons costs $2.04 or $2.34, depending on the size. Panty liners cost $1.22 or $1.33. In many cases, these prices are significantly higher than what one would pay at their local grocery or drug store. Prisoners are advised that prices in the canteen are subject to change “without notice”.[32] If a prisoner cannot or does not order items from the canteen, she cannot obtain these items from another source, including other prisoners or outside donations by friends, families, or community groups.

Reproductive Health

Being in prison does limit many freedoms, but it does not restrict all rights. Included in the rights that are retained while a woman is in prison, is the right to decide whether to continue a pregnancy. Courts, including the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals that includes Nebraska, have consistently held that women retain the right to have an abortion if they are incarcerated. [33] Nationwide, it is estimated that 6 to 10% of women who enter prison or jail are pregnant.[34]

In Nebraska, there are presently no state statutes or regulations regarding the provision of abortion services for incarcerated women. Nebraska state officials do not track the number of pregnant prisoners who enter the prison system or become pregnant while serving sentences.

Sexual Assault

Many incarcerated women were sexually assaulted or suffered similar trauma prior to their entry into the prison system. 80% of women in U.S. prisons suffered severe violence as girls, and 75% were abused by an intimate partner when they were adults.[35] A more recent study indicates that this number is likely higher. In August 2016, the Vera Institute of Justice found that 86% of women in jail report having experienced sexual violence in their lifetime.[36]

Spending time in custody can be traumatizing for all, but it can be particularly traumatizing for women survivors of domestic or sexual assault. Many standard correctional procedures can be a trigger for painful or repressed memories and can result in emotional symptoms of depression or Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). Routine searches, the use of restraints, and the non-private nature of life in prison can cause victims to re-experience personal trauma. Doing typically private things, such as dressing, showering, or using the restroom in a public, monitored environment can trigger trauma for sexual assault or abuse survivors. Typical reactions that a trauma survivor might have to such stressors, including withdrawal or anger, may result in disciplinary sanctions being imposed. These sanctions can include solitary confinement or similar isolation which can further traumatize these prisoners. As stated above, counseling and support for sexual assault survivors is lacking in many prisons and jails.

In addition to the trauma that former sexual assault victims experience with prison life, some prisoners experience sexual assault while in prison. To address the nationwide problem of sexual assault in prison, Congress passed the Prison Rape Elimination Act (PREA) in 2003. The goals of the PREA are to eliminate sexual abuse in confinement. The law applies to federal and state prisons and local jails. Correctional facilities are to screen all arrestees/detainees to determine risk of sexual abuse at intake and to respond appropriately to sexual assault incidents within the facilities. Each facility is to have a written policy or procedure which must be approved by the U.S. Department of Justice.

When Congress passed the PREA, it required states to certify that they would comply with the standards set by the Department of Justice (DOJ). A handful of states, including Nebraska, could not initially certify that they would comply with the standards in 2014.[37]

On March 31, 2016, Nebraska Governor Pete Ricketts issued an assurance to the DOJ that Nebraska will use at least 5% of any grants to achieve full compliance with the PREA. Nebraska is one of 42 jurisdictions that issued similar assurances in 2016. 10 states issued certifications that they were compliant with the PREA. Two states, Arkansas and Utah, have opted out of PREA compliance efforts.

The PREA contains a number of standards for prisons and jails to meet. The standards generally address issues relating to the prevention, detection and response to sexual assault of prisoners. Towards the ostensible goal to become compliant with the PREA, NDCS issues an annual assessment reporting numbers of complaints or investigations and the outcome of those investigations. NDCS states that it “has a zero tolerance policy” regarding sexual assault, sexual abuse, or sexual harassment of prisoners or staff.

In 2016, NDCS partnered with the Nebraska Coalition to End Sexual and Domestic Violence to provide prisoners with a resource to report or discuss incidents of sexual assault or abuse. The 2016 PREA Assessment report showed that 157 contacts were made, which included crisis line calls. At NCCW, 13 investigations of sexual assaults or sexual harassment incidents were conducted. The majority, 12, of these were determined to be “unsubstantiated” or “unfounded”. Not a single report or investigation from any Nebraska prison facility, including the NCCW, was referred to the local county attorney for prosecution. This includes the other facilities that house women, CCC-L and CCC-O, which also had no referrals for prosecution.

Recommendations for Reform

1) Alternatives to arrest and incarceration

One way to prevent women from ending up in prison is through reform in police practices, including changing which offenses result in arrests. Prioritizing policing on lower-level offenses, particularly drug offenses, has contributed to the increase in women in the criminal justice system. A greater focus on minor offenses increases the likelihood that women will be arrested and jailed. Even a few days in jail increases the probability that an offender will end up serving more time in custody. Law enforcement and prosecutors should implement options and alternatives to jailing offenders. Some communities have diversion programs that are designed to treat those who are suffering from trauma, substance use, or mental health deterioration through alternatives to jailing them. These programs often work with a public mental health system or similar entity trained to address mental health crisis situations.[38]

Crisis intervention team programs can be beneficial for diverting women from prison, given the high percentage of female offenders who live with a mental illness.[39] In recent years, the Omaha Police Department has been working with the Douglas County Crisis Response Team, a 24/7 program that provides therapists and assistance to law enforcement should they respond to a call involving someone who is mentally ill. Of the 1,193 behavioral health forms, or referrals to the Crisis Response Team for 2014-15, only 1.8% resulted in arrest while the large majority were referred or transported to a treatment facility.[40] Ultimately, the decision to contact the Crisis Response Team is up to the responding officers. Continued training and education will ensure that this program is effectively used. This is a good model worthy of exploration by other communities.

Reforms to Nebraska’s debtors’ prison should be implemented with all deliberate speed. Nebraska recently enacted bond reform to avoid unnecessary pretrial detention by requiring courts to consider an individual’s financial ability to post a money bond and broadened the authority of courts to release defendants under supervision. [41]

One significant, yet simple, reform to the problems women face in prison would be to avoid sending women to prison. As in other Smart Justice reforms, policymakers should invest in meaningful alternatives to prison such as drug courts, veterans’ court, mental health courts, and similar problem-solving focused courts.

2) Improve access to meaningful programming and services in prison to improve quality of life and support successful re-entry

Proper programming and services in prisons are vital to the successful reentry of female prisoners. Access to basic health care including mental, physical, dental and behavioral health services must be provided in the same manner as the community standard of care under Nebraska state law.[42] Drug treatment is critically important for female prisoners because they are significantly more likely to have a drug problem, a mental health diagnosis, or some similar dual diagnosis.

3) Improve Access to Supportive Services for Trauma Survivors

Nebraska should explore toll free hotlines and other practices to address gaps in the provision of services for trauma survivors who are incarcerated.[43]

4) Provide meaningful contact with children

Nebraska should maintain and broaden programs that encourage and facilitate meaningful, healthy relationships with mothers and children.

Across the country, some jails have developed parenting classes and parental support to help mothers prepare for reunification. For instance, in San Francisco, a nonprofit entity provides services directly in the jail such as parental education, therapeutic visitation, contact visitation and assistance in reentry and reunification upon release.[44]

To maintain regular contact between parent and child, policies that provide for meaningful visitation should be implemented. Some jails across the country allow for regular, such as weekly, contact visits between prisoner-parents and their children. Allegheny County, Pennsylvania operates the Family Support Program, which similarly accommodates contact visits between prisoner, usually women, and their children.[45]

One way to reduce barriers to contact with children short of providing for contact visits is to lower the costs of telephone calls from jails. While the costs of phone calls from the state prisons are not cost-prohibitive, the costs at the county level for jails can be very costly.

5) Provide free feminine hygiene products for women prisoners, following the federal lead.

A simple reform for women’s health would be for policymakers to emulate the federal Bureau of Prisons and provide free feminine hygiene products. [46] This could be done by administrative directive, or it could be accommodated by legislative action by state senators.

Nebraska prisons’ rules and regulations should be updated to ensure clarity in respecting a woman’s right to terminate a pregnancy while incarcerated.

A comprehensive reproductive justice framework is needed to address a plethora of issues. Pregnant women should not be subjected to solitary confinement. Anti-shackling laws for pregnant prisoners during pregnancy, birth, and post-partum are needed. An examination on existing prenatal care standards including accommodations for clothing, nutrition, care, labor and delivery is necessary. An examination of rules and regulations to ensure breastfeeding and lactation support should also be made a priority.

Conclusion

In consideration of extreme overcrowding throughout Nebraska’s prisons, pending litigation, and other factors, prison reform will remain a top agenda item for Nebraska leaders. As such, the time is ripe for policymakers in Nebraska to conduct further review and analysis of the needs of women in our prisons. Leaders should explore the above policy reform solutions to ensure the unique needs of incarcerated women are being addressed in compliance with best practices in law and policy.

[1] NDCS Quarterly Data Sheet, June 2017

[5] NDCS Quarterly Data Sheet, June 2017

[6]http://nebraskalegislature.gov/FloorDocs/104/PDF/Agencies/Correctional_Services__Department_of/628_20161230-121647.pdf; https://www.usnews.com/news/best-states/nebraska/articles/2017-09-28/nebraska-adds-beds-space-for-work-release-prisoners

[7] Correctional Populations in the United States, 2013-Bureau of Justice Statistics-published December 29, 2014.

[8] Vera Institute for Justice, “Overlooked: Women and Jails in an Era of Reform” August 2016.

[9] State Incarceration Rates, http://www.sentencingproject.org/the-facts/#map?dataset-option=SIR

[10] NDCS Quarterly Data Sheet, April-June 2017] Sickmund, M., Sladky, M. Kang, T.J., and Puzzanchera, C. (2015). Easy Access to the Census of Juveniles in Residential Placement. Washington, D.C.: Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention.

[11] Lawrence A. Greenfeld and Tracy L. Snell, Women Offenders U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics 2014

[12] “Nebraska QuickFacts from the US Census Bureau” https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/NE,US#viewtop Retrieved August 30, 2017

[13]2016 Annual PREA Assessment, Nebraska Department of Correctional Services Report

[14] National Resource Center on Justice Involved Women, 2016. http://cjinvolvedwomen.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/Fact-Sheet.pdf

[15] Id.

[16] Id.

[17] Id.

[18] 2014 Department of Correctional Services Annual Report https://www.corrections.nebraska.gov/sites/default/files/files/46/2014_ndcs_annual_report_reduced.pdf

[19] Susan W. McCampbell, “The Gender-Responsive Strategies Project: Jail Applications” U.S. Department of Justice, National Institute of Corrections, 2005

[20] “A Shared Sentence” Kids Count, April 2016 Policy Report

[21] Young, D. “Health Status and Service Use Among Incarcerated Women” Family and Community Health 1998; 21(3):16-31.

[22] Maruschak, LM. Medical problems of state and federal prisoners and jail inmates, 2011-12. Washington: Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2015.

[23] Fearn NE, Parker K. Health care for women inmates: Issues, perceptions, and policy considerations. California Journal of Health Promotion 2005; 3(2):1-22.

[24] Sabata v. Nebraska Department of Correctional Services, 4:17-cv-03107 (Dist. Ct. Neb.), filed August 15, 2017.

[25] US Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, “Indicators of Mental Health Problems Reported by Prisoners and Jail Inmates 2011-12” June 2017”, Jennifer Bronson and Marcus Berzofsky

[27] NDCS Quarterly Data Sheet, June 2017.

[28] Sabata v. Nebraska Department of Correctional Services, 4:17-cv-03107 (Dist. Ct. Neb.), filed August 15, 2017.

[31]US Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Prisons, Operations Memorandum 001-2017 “Provision of Feminine Hygiene Products”

[32] NCCW Canteen August 1, 2017

[33] Roe v. Crawford, 514 F3d 789 (2008)

[34] Sabol WJ and Minton TD, Prison and Jail Inmates at Midyear 2006, Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, 2007, Table 13

[35] Correctional Association of New York at http://www.correctionalassociaton.orgissue/domestic-violence

[36] See also Shannon M. Lynch, “Women’s Pathways to Jail: The Roles and Intersections of Serious Mental Illness and Trauma” U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Assistance, 2012

[37] http://journalstar.com/news/state-and-regional/nebraska/heineman-says-state-can-t-comply-with-prison-rape-elimination/article_fe8b1fdd-0cb1-5194-8ce7-4b01360b231c.html

[39] Jennifer L.S. Teller, “Crisis Intervention Team Training for Police Officers Responding to Mental Disturbance Calls” Psychiatric Services (2006)

[40] http://www.omaha.com/livewellnebraska/omaha-police-have-options-on-mental-health-calls-but-available/article_676485ec-9db7-547b-aa84-d796cd33abdd.html

[41] See LB 259, 2017 http://nebraskalegislature.gov/bills/view_bill.php?DocumentID=31423

[42] Neb.Rev.Stat. §83-4,155 (Reissue 2008).

[44] Community Works, “One Family”

[45] Bryce Peterson, “Toolkit for Developing Family-focused Jail Programs”, Urban Institute, 2015

Documents

Related content

ACLU: Tampons and Pads Are Treated as a Luxury Item by Nebraska...

October 19, 2017

The Prison Lawsuit: David vs. Goliath

January 8, 2019ACLU Files Court Challenge to State of Nebraska’s Execution Protocol

March 26, 2018

Title X in Nebraska

March 20, 2018Nebraska Is Illegally Obtaining and Storing Execution Drugs in...

March 12, 2018ACLU Statement on Dept. of Corrections Issuing of a Death Notice

January 19, 2018ACLU Applauds Introduction of Bill Limiting Solitary Confinement...

January 5, 2018