Table of Contents

Executive Summary | What the Experts Say | Method | Findings | Agencies Meeting Gold Standard | Recommendations

The ACLU and Police Accountability

The ACLU of Nebraska is a non-profit, non-partisan organization that works to defend and strengthen the individual rights and liberties guaranteed in the United States and Nebraska Constitutions through a sophisticated program of integrated advocacy with strategies that include litigation, negotiation, policy research, and public education. In 2016 we are proudly celebrating our 50th anniversary and are supported by over 2,000 members and about 6,000 supporters stretching far across our great state.

Police have the vital and difficult job of protecting public safety. Performing this job effectively does not require sacrificing civil liberties. The policies and actions of the police are instrumental in deciding who gets stopped, searched, arrested, and funneled into the criminal justice system; indeed, the United States' overincarceration crisis begins at the front end of the system. Meanwhile, often under the guise of our failed drug war, concerns over treatment of people of color are rampant, and federal grant programs enable the increasing militarization of local police departments.

In Nebraska, the ACLU has successfully worked to create mandatory training for law enforcement and has worked with specific departments on anti-bias trainings. As a government watchdog the ACLU periodically analyzes practices of individual law enforcement agencies such as their use of Tasers, civilian complaint procedures, and racial profiling practices to ensure our local agencies are meeting best practices in law and policy.

Executive Summary

The unique position of power and authority that members of law enforcement hold means that there is an added need to uphold high ethical standards and accountability to the community that a department is sworn to serve and protect. One officer who engages in misconduct or abuse of power can sully the reputation of the entire profession. It is imperative for executives to consistently maintain a culture of integrity and community trust throughout their departments every day.

U.S. Department of Justice[i]

Clear, accessible and welcoming complaint processes will build trust between the community and law enforcement and permit leadership to identify problems before they arise. With adoption of best practices, Nebraska law enforcement can ensure their good work is appreciated and understood by the public.

We are undergoing a nationwide conversation about policing right now. Law enforcement officers who risk their lives every day with valor and integrity as well as communities of color who worry about the safety of their children have a common goal: we must advance a positive dialogue to improve police-community relations.

This is why the ACLU of Nebraska chose to re-examine how accessible and transparent local law enforcement agencies are in the area of civilian complaints. In 2014, ACLU surveyed 31 of the largest police and sheriff departments in the state. We examined their websites and interactions with the public to determine how an average civilian might submit a concern or complaint to the Chief of Police or Sheriff. In 2014 our survey revealed that only 8 of the 31 agencies had any online information at all, and several departments could not answer basic questions related to civilian complaint procedures during a phone survey.

In 2016 the local landscape has dramatically improved. The good news for Nebraska is that more agencies have moved towards meeting the best practice recommendations of the US Department of Justice. There have been significant improvements by many Nebraska agencies that deserve high commendation.

Civilian complaints may be about relatively small infractions: perhaps a civilian has witnessed an officer driving poorly, using abusive language, or getting free perks at a local business. Some complaints may be more serious: perhaps it is a charge of racial profiling or using excessive force during an arrest. In either category, law enforcement leadership should pave an easy path to hear concerns by including clear information to the public.

Complaint procedures that are clearly spelled out and very accessible to the public send a positive message and promote police accountability. Both are vital to the maintenance of public trust in law enforcement.

In the following report, ACLU compared U.S. Department of Justice recommendations to current local practice. We have presented expert recommendations on best practices so those agencies who have not made improvements have a clear roadmap for moving forward.

To encourage strong bonds of trust between law enforcement and the community, the U.S. Department of Justice recently unveiled a three-part series of guidance.[ii] The repeated message: make police more approachable, listen to the concerns of the community, open lines of communication, focus on relationships with communities of color. Civilian complaint processes are one of the simplest steps an agency can take to open up lines of communication between law enforcement and the public.

According to the International Association of Chiefs of Police (IACP), the unethical work of one officer can severely undermine the work of thousands of his or her ethical colleagues; community trust is "key to effective policing" and the assurance of a department's "honesty, integrity, legitimacy, and competence."[iii]

There are three primary guidelines for complaint processes to ensure the maintenance of public trust in law enforcement. These recommendations have been developed by the Department of Justice’s COPS and IACP. These experts have produced three primary guidelines for complaint processes to ensure the maintenance of public trust in law enforcement.[iv]

Requiring complaints to be made in person, limiting deadlines for filing a complaint, or limiting the process to business hours may discourage civilians with valid concerns from coming forward. Additionally, threats that false statements could lead to prosecution needlessly unnerve complainants, despite the fact that false complaints are rare.[viii] Law enforcement agencies should not actively discourage the filing of complaints.[ix] This creates the perception that police departments wish to cover up misconduct. Instead, law enforcement agencies should actively encourage civilians to file complaints if they believe misconduct has occurred in order to promote accountability and maintain community trust.

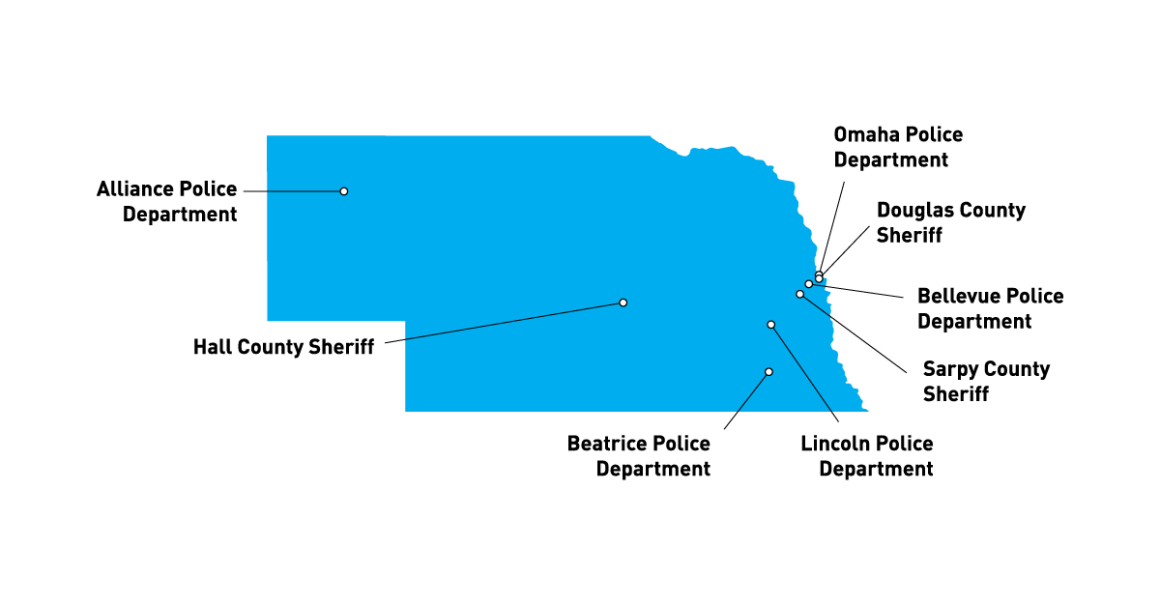

For this report, in July 2016, the ACLU of Nebraska first conducted a review of websites for some of the largest law enforcement agencies in Nebraska to gauge the accessibility of police complaint processes.

We surveyed the following municipal police departments: Alliance Police, Ashland Police, Beatrice Police, Bellevue Police, Columbus Police, Falls City Police, Fremont Police, Grand Island Police, Kearney Police, Hastings Police, Lexington Police, Lincoln Police, Norfolk Police, North Platte Police, Omaha Police, Plattsmouth Police, Scottsbluff Police, Seward Police, Wayne Police.

We surveyed the following county sheriffs: Adams County Sheriff, Buffalo County Sheriff, Dodge County Sheriff, Douglas County Sheriff, Gage County Sheriff, Hall County Sheriff, Lancaster County Sheriff, Madison County Sheriff, Sarpy County Sheriff, Scotts Bluff County Sheriff, Seward County Sheriff.

Finally, we surveyed the Nebraska State Patrol, making a total of 31 agencies in the survey.

The ACLU of Nebraska evaluated whether the websites had clear information on the complaint process, whether there were multiple ways to submit a complaint, and whether there was any intimidating language that might discourage complaints.

Finally, ACLU volunteers called the selected agencies to ask “What is the complaint process for someone with a concern?” to determine how such a caller is treated. The goal of the website review and phone calls was to replicate what the average Nebraskan would experience if she wanted to report a concern.

Website Survey

Commendations belong to several agencies who improved their existing good website information from 2014 as well as to several agencies who created website information following our 2014 report.

In 2014, only 8 agencies had any information online at all. We are very pleased to report that number has increased to 14 so the following agencies have at least some information online to advise the public how to file a complaint or concern:

- Alliance Police

- Beatrice Police

- Bellevue Police

- Fremont Police

- Kearney Police

- Lincoln Police

- Omaha Police

- Scottsbluff Police

- Douglas County Sheriff

- Gage County Sheriff

- Hall County Sheriff

- Lancaster County Sheriff

- Sarpy County Sheriff

- Nebraska State Patrol

The results of this survey are heartening. Real progress is being made towards meeting best practices when a civilian has a concern or a complaint about law enforcement. The ACLU of Nebraska hopes that by recognizing this positive work by so many agencies in our great state that other agencies that have not had the time or opportunity to establish online information in this regard are inspired by these many examples from their peers about how they too can establish civilian complaint information online.

OMAHA POLICE: Particular commendation goes to the Omaha Police Department. OPD formerly had an intimidating warning on their complaint form during the 2014 survey. The 2016 research revealed that this language had been removed and that OPD provides a clear outline of the process, makes materials available in Spanish, and utilizes accessible methods of complaints now fully meeting the DOJ gold standard for civilian complaints.

DOUGLAS COUNTY SHERIFF: Sheriff Timothy Dunning also deserves particular commendation for meeting the DOJ best practices. The Douglas County Sheriff’s website has actively encouraging language seeking to elicit concerns from the public, it clearly explains their complaint process, offers several methods to submit a complaint, and explicitly promises there will be no retaliation for a complaint. Further, since 2014, Sheriff Dunning has conducted training of all personnel to ensure civilians will be treated respectfully if they make a complaint.

Public trust with the community we serve is vital to the success of every law enforcement agency. An open and transparent complaint process is central to building and maintaining that trust, and it reinforces accountability within the agency. As an accredited agency, we proactively evaluate our policies and procedures and make changes that reflect national best practices. – Timothy Dunning, Douglas County Sheriff

ALLIANCE POLICE: Alliance Police Department earned praise in our 2014 report and they have become even more accessible and welcoming. There are multiple methods to submit a concern, the process is clearly explained to the public, there is an explicit promise that there will be no retaliation, and the department promises to “thoroughly investigate” complaints.

BEATRICE POLICE: Beatrice Police Department added complaint information to their website since 2014. They’ve adopted the DOJ best practices, as they accept anonymous complaints, permit people to submit concerns in several different ways, welcome third party complaints, and the site clearly describes the process that follows after a complaint.

BELLEVUE POLICE: Bellevue Police Department had good information available online in 2014 and continues to provide a link on the front page of their website that directs people to complaint information. Complaints are accepted in several ways.

LINCOLN POLICE: Lincoln Police Department earned the highest praise in our 2014 report, and they remain one of the most accessible and welcoming civilian complaint processes in the state. LPD deserves particular commendation for making their forms available in Arabic and Vietnamese as well.

HALL COUNTY SHERIFF: Hall County has added complaint information to their website since 2014, promises to address all concerns “with serious consideration,” and follows DOJ best practices by even permitting anonymous complaints.

SARPY COUNTY SHERIFF: In 2014, Sarpy County was meeting all aspects of the DOJ recommendations, including having Spanish language materials. They continue to provide multiple methods of complaint submission and a very clear and accessible explanation of the process to allay public concerns.

Say thanks to these law enforcement agencies

Concerns

Unfortunately, a few agencies have failed to improve poor practices we noted with concern in 2014 and a few agencies in fact moved towards being less accessible than they were several years ago.

Agencies only accepting compliments: Columbus Police[x] and Grand Island Police[xi] both have robust websites with a specific mechanism to submit compliments about police—but lack any information whatsoever about how to submit a concern or complaint. It is entirely appropriate that these and other agencies have a process in place to receive positive information about an individual officer’s good works in the community. However, we believe that civilian oversight and accountability is best met when similar processes are equally provided for civilian complaints.

Little or no information: Fremont Police[xii] and Kearney Police[xiii] both deserve commendation for adding some information since 2014, but both essentially only have a single sentence inviting the public to contact the department with a complaint. Neither explains the process.

Threats of prosecution: Gage County and Scottsbluff Police have complaint information on their website with substantial information about the process. However, Gage County has set an arbitrary 30 day time limit and contains the intimidating threat of prosecution. Civilians must sign a statement that says “Knowingly giving false information to a Law Enforcement Officer is a punishable offense under 28-9071(a).”[xiv] Scottsbluff Police warn “If you intentionally make a false report to this department, you should know that making a false report could result in criminal and/or civil legal proceedings being filed against you.”[xv] The DOJ specifically advises agencies to eliminate such threats—the average civilian might worry “If I complain about a he-said-she-said situation that I can’t prove, will that expose me to jail time?” Law enforcement leadership should have the ability to quickly dismiss unfounded complaints as appropriate without utilizing language identified as potentially problematic by the DOJ.

Inaccessible: It is disappointing to see the Nebraska State Patrol has moved away from DOJ best practices during the most recent survey of agencies. In 2014, NSP had a webpage that invited civilians to communicate in a variety of ways to ensure accessibility: it permitted complaints to be submitted in person, by phone, or mail and provided all necessary contact information to reach Patrol leadership. Unfortunately, NSP now only has an online form that inexplicably requires date of birth, no information about the complaint process, and no possibility for anonymous complaints.[xvi] People who do not wish to share their email or phone are barred from using the form, which requires all fields to be populated with information. In other words, the Patrol has moved away from DOJ recommendations and become significantly less accessible.

Ask these law enforcement agencies to improve complaint procedures

Telephone Survey

An ACLU volunteer phoned the same 31 agencies to ask a simple question: “What is the process for filing a complaint against an officer?” The volunteer was trained to not imply she had a complaint, and if asked, openly stated she had no complaint in order to ensure there was no misunderstanding.

The same barriers that might discourage someone reviewing police websites were repeated in the phone survey experience. One rural agency informed our volunteer “You have to pick up the form to file a complaint in person,” which would limit many people’s ability to follow up and possibly intimidate others.

The good news is that our volunteer generally reported that the 31 surveyed agencies were cordial and professional, even when they encountered employees who were not well versed in these issues. This contrasts with our 2014 survey, where our volunteer callers found some agencies refusing to provide any information on the phone.

Ongoing professional development and training within departments can ensure that every employee knows how to respond to a civilian complaint. Law enforcement leadership can follow the cue of the Douglas County Sheriff’s recent all-staff training to make sure concerns are addressed appropriately and directed to the right member of the organization for review.

All Nebraskans deserve to feel safe and protected by law enforcement, and accountability is an essential ingredient to maintaining the public trust. We suggest that every law enforcement agency in Nebraska adopt the following recommendations to improve their complaint processes.

- Add civilian complaint information to agency websites. Many agencies in Nebraska maintain a website but have no information about their complaint process on their websites. Law enforcement agencies should make information on complaint procedures and policies easy to find on their websites as well as through brochures available in public places.

- Allow complaints to be submitted in any form. Requiring complaints to be filed in person or via forms that require specific identifying information such as date of birth can quickly discourage potential complainants. Accepting complaints via email, mail, phone, or fax enables civilians to submit their complaints in the manner they find most appropriate.

- Accept complaints from anyone. Experts stress the importance of accepting anonymous and third-party complaints, as well as complaints from minors, in order to ensure that any incidents of potential misconduct are investigated. Additionally, law enforcement agencies should refrain from imposing arbitrary time limits on complaint submissions.

- Refrain from intimidating potential complainants. Complainants, who may already be wary of law enforcement, may be deterred by unnecessary threats of prosecution or immigration consequences. Fear of retaliation can influence civilians who may have valid concerns about police misconduct to not file their complaints.

- Provide training for all staff. Frontline staff responsible for law enforcement action in the streets as well as office staff should know how to take a civilian concern and direct it appropriately to reach leadership.

Conclusion

While much work remains to ensure full compliance with best practices statewide much progress has been made over the past two years. That is good news to inspire us all to action and to do better by each other during these difficult times.

Acknowledgements

Appreciation to Madison Wurtele and Kelli Yost, UNL student researchers, and Marin Krause, B.A., who all contributed to this project.

|

|

Has Information Online

|

Multiple Ways to Submit Complaint

|

Complaint Process Is Free of Threats

|

Complaint Information in Multiple Languages

|

|

Alliance Police

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

No

|

|

Ashland Police

|

No

|

No

|

No

|

No

|

|

Beatrice Police

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

No

|

|

Bellevue Police

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

No

|

|

Columbus Police

|

No

|

No

|

No

|

No

|

|

Falls City Police

|

No

|

No

|

No

|

No

|

|

Fremont Police

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

No

|

|

Grand Island Police

|

No

|

No

|

No

|

No

|

|

Hastings Police

|

No

|

No

|

No

|

No

|

|

Kearney Police

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

No

|

|

Lexington Police

|

No

|

No

|

No

|

No

|

|

Lincoln Police

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

|

Norfolk Police

|

No

|

No

|

No

|

No

|

|

North Platte Police

|

No

|

No

|

No

|

No

|

|

Omaha Police

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

|

Plattsmouth Police

|

No

|

No

|

No

|

No

|

|

Scottsbluff Police

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

No

|

No

|

|

Seward Police

|

No

|

No

|

No

|

No

|

|

Wayne Police

|

No

|

No

|

No

|

No

|

|

Adams Co. Sheriff

|

No

|

No

|

No

|

No

|

|

Buffalo Co. Sheriff

|

No

|

No

|

No

|

No

|

|

Dodge Co. Sheriff

|

No

|

No

|

No

|

No

|

|

Douglas Co. Sheriff

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

No

|

|

Gage Co. Sheriff

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

No

|

No

|

|

Hall Co. Sheriff

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

No

|

|

Lancaster Co. Sheriff

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

No

|

|

Madison Co. Sheriff

|

No

|

No

|

No

|

No

|

|

Sarpy Co. Sheriff

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

|

Scotts Bluff Co. Sheriff

|

No

|

No

|

No

|

No

|

|

Seward Co. Sheriff

|

No

|

No

|

No

|

No

|

|

NE State Patrol

|

Yes

|

No

|

Yes

|

No

|

[i] Building trust, supra, at 37.

[iii] U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Community Oriented Policing Service, Building trust between the police and the citizens they serve: An internal affairs promising practices guide for local law enforcement, page 3, (2010) available at http://www.theiacp.org/portals/0/pdfs/buildingtrust.pdf

[viii] Building trust, supra, at 86-87.

Date

Sunday, August 21, 2016 - 10:15am

Featured image

Show featured image

Hide banner image

Related issues

Police Practices

Documents

Show related content

Pinned related content

Local Agencies included in Civilian Complaint Survey

Law Enforcement Accountability

Tweet Text

[node:title]

Share Image

Type

Style

Standard with sidebar

Juvenile Solitary Confinement in Nebraska

Introduction

The ACLU of Nebraska is a non-profit, non-partisan organization that works to defend and strengthen the individual freedoms and civil liberties guaranteed in the United States and Nebraska Constitutions through policy advocacy, litigation and education. We serve over 2,000 members and supporters throughout our great state and represent more than 500,000 members nationwide.

The ACLU is committed to protecting the constitutional rights of juveniles in detention. The use of solitary confinement violates juveniles’ rights under the following theories:

- US Constitution 8th Amendment prohibition of cruel and unusual punishment

- US Constitution 5th Amendment guarantee of due process

- US Constitution 14th Amendment guarantee of due process

- Nebraska State Constitution Article I-9 prohibition of cruel and unusual punishment

- Nebraska State Constitution Article I-3 guarantee of due process

- Americans with Disabilities Act

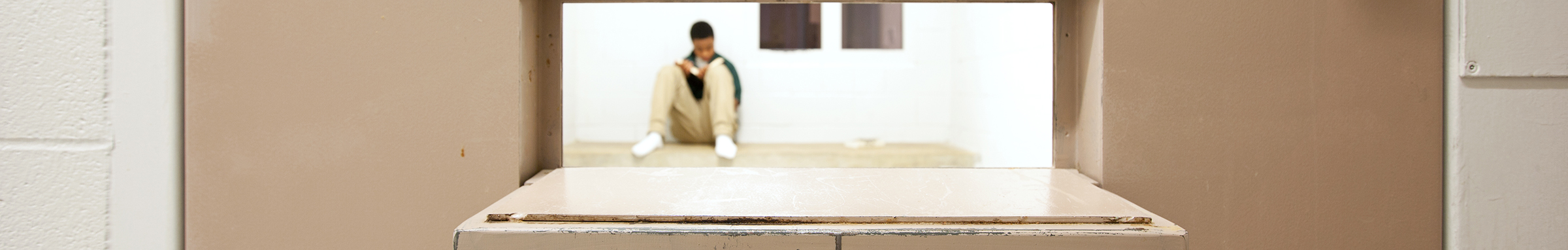

On any given day in Nebraska, juvenile justice facilities routinely subject kids in their care to solitary confinement. The solitary confinement of children is suspect from a legal and policy perspective. Solitary confinement can cause extreme psychological, physical, and developmental harm. For adults, the effects can be persistent mental health problems, or worse, suicide. And for children, who are still developing and more vulnerable to irreparable harm, the risks of solitary are magnified – protracted isolation and solitary confinement can be permanently damaging, especially for those with mental illness. It is time to scrutinize the use of solitary confinement on children. Nebraska should strictly limit and uniformly regulate isolation practices to ensure our state comports with best practices that provide positive outcomes for vulnerable youth and to ensure Nebraska quickly remedies potential systemic legal issues.

Dylan spent 10 to 12 hours locked away from other youth when he was 14 and in an Omaha psychiatric facility. Read more of his story.

Report Overview

Before they are old enough to get a driver’s license, enlist in the armed forces, or vote, some children in Nebraska are held in solitary confinement for days, weeks—and even months. This practice occurs in every Nebraska juvenile justice facility, to varying degrees, but the overarching theme of over-use is consistent throughout the state. On any given day in Nebraska, juvenile justice facilities routinely subject the kids in their care to solitary confinement. Like adult prisons, juvenile facilities sometimes employ the most counterproductive and inhumane correctional practices—including extended periods of solitary confinement, room restriction, isolation, segregation, and seclusion. Isolation practices frequently involve placing a youth alone in a cell for several hours, sometimes for multiple days; restricting contact with family members; limiting access to reading and writing materials; and providing limited educational programming, recreation, drug treatment, or mental health services.

Throughout this report, “solitary confinement” refers to any physical and social isolation of children in juvenile detention facilities. It does not refer to short intervention “time out” practices used to help a juvenile manage current acting out behavior.

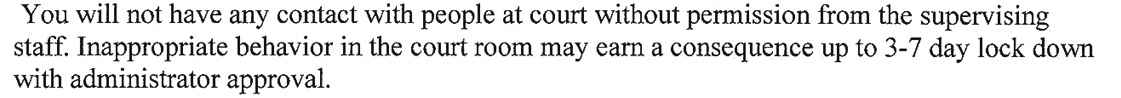

While temporary use of seclusion for a youth may be necessary to maintain the safety and security of that youth or other people, the use of solitary confinement on children in Nebraska is clearly overused, and can cause much more serious problems than those it is supposedly employed to solve. Additionally, our research has uncovered that frequently the reasons why young people are placed in solitary confinement can be for even relatively minor offenses, such as talking back to staff members, having too many books, or refusing to follow directions. This research gives rise to the concern that juvenile facilities in Nebraska are not utilizing best practices for the use of solitary confinement and thus are risking serious mental health impacts for vulnerable youth.

The ACLU of Nebraska generated the idea for this research in concert with a growing national conversation about the very specific harms of solitary confinement on juvenile brain development. Mental health professionals have established that the negative psychological impacts of solitary on the adult brain are greatly magnified on the developing juvenile brain and can lead to permanent damage. The American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatrists oppose the use of solitary confinement for juveniles.1 Experts at the Juvenile Detention Alternatives Initiative recommend a juvenile be placed in solitary for no longer than four hours.2

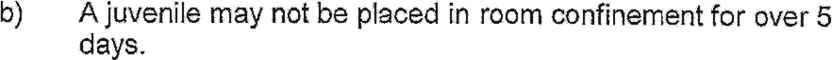

Our partners at Voices for Children recently completed a multi-year study of the two youth centers run by the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) at Geneva and Kearney.3 Their findings show these facilities are making some progress to decrease the average stay in solitary confinement but both facilities are still far in excess of best practices. For example, some facilities are holding children up to five days in restricted settings without peer contact, as described later in this report.

While vitally important, this research of state facilities does not tell the full story of youth solitary confinement in Nebraska since it was limited to only the two DHHS-operated facilities. In 2015 the ACLU of Nebraska decided to conduct more comprehensive statewide research regarding all of the remaining juvenile detention centers in Nebraska to determine what, if any, their written policies are and their actual practices in regards to the use of solitary confinement.

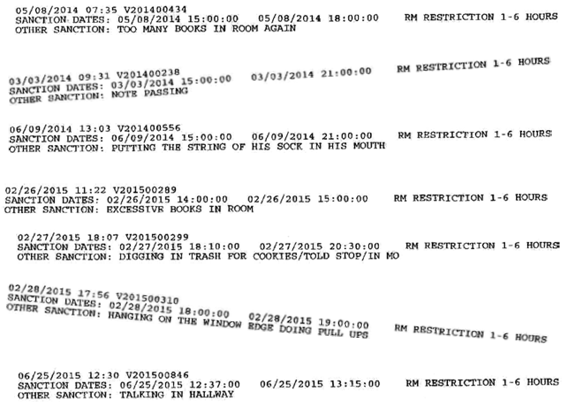

There are two other state facilities—the Nebraska Department of Corrections houses young male offenders at the Nebraska Correctional Youth Facility and houses young female offenders at the York Correctional Center for Women. There are also five county facilities located in Douglas County, Lancaster County, Sarpy County, Northeast Nebraska Juvenile Services in Norfolk, and Scotts Bluff County.

The results of our research demonstrates that these facilities are using solitary far more frequently and for far longer periods than their DHHS counterparts and far in excess of best practices. This report explains how solitary confinement harms children, catalogs solitary confinement policies used by Nebraska’s juvenile detention facilities, and outlines a path to reform that would decrease the use of solitary confinement in juvenile detention centers because we can and we must do better for our vulnerable youth in Nebraska.

Existing Nebraska Landscape

Nebraska far exceeds the national average for the number of youth residing in juvenile detention, correction, or residential facilities. In fact, Nebraska has the third highest per capita number of youth in juvenile facilities as ranked by the Annie E. Casey Kids Count Data Center.4 Additionally, our research reveals that Nebraska is also an outlier in terms of policies that permit lengthy periods of solitary confinement, with one shocking example of a policy allowing for the use of solitary for up to 90 days. Even more disturbing, some facilities surveyed have no policies governing solitary confinement or data to track usage of solitary confinement. As described below, most of Nebraska’s neighboring states restrict the use of solitary for youth along a range of 24 hours to 5 days.

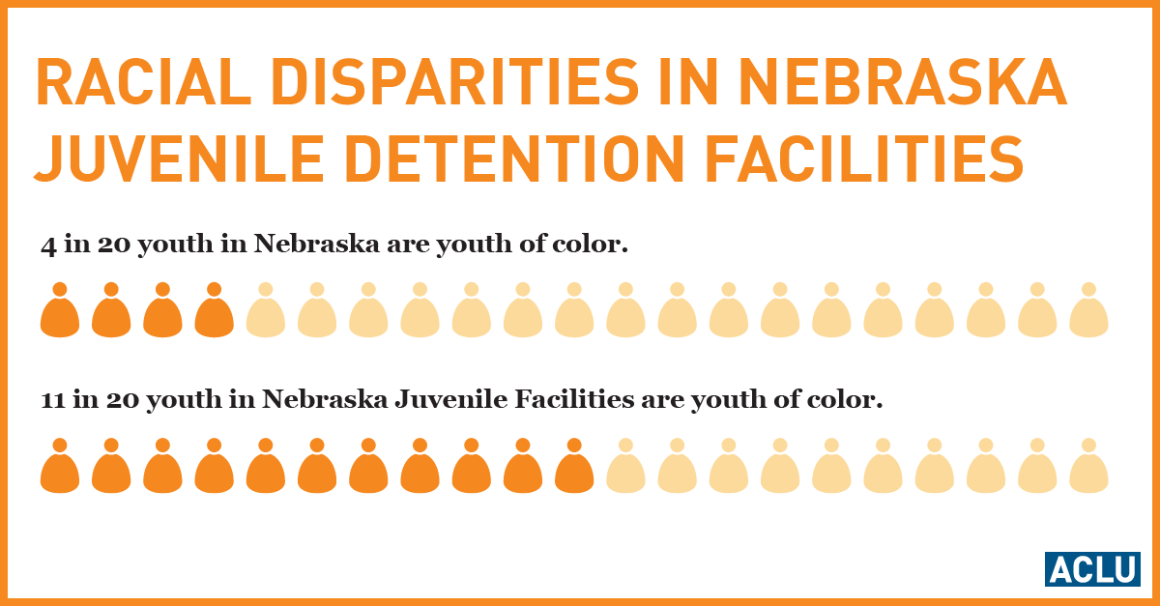

Approximately 8,000 juvenile cases are reported to the Nebraska Crime Commission each year.5 Thus, reform in this area is critical to improving the quality of life for the hundreds of vulnerable Nebraska children in detention facilities within the juvenile justice system.6 It is also important to note that the juvenile justice system has disproportionate impacts among communities of color: 55% of juveniles in detention in our state are children of color.7

Many young Nebraskans who are presently detained are not public safety threats and could potentially be rehabilitated through much less restrictive means or at the very least should not be subjected to mental anguish during their period of detention. These conditions of confinement can have long lasting effects on their ability to successfully transition back into their families, our communities, and the economy.

Lisa was placed in solitary confinement in an Omaha psychiatric facility after threatening self-harm at age 14. Read more of her story.

The Overuse of Solitary Confinment Harms Nebraska Children

The overuse of solitary confinement for children is highly suspect from both a legal and policy perspective. Solitary confinement can cause extreme psychological, physical, and developmental harm. For adults, the effects can be persistent mental health problems and even result in suicide. Children are more vulnerable as they are still developing physically and mentally-thus, the risks and impacts of solitary are magnified and more pronounced – particularly for kids with disabilities or kids with histories of trauma and abuse. The research cited below draws heavily from two national ACLU reports on juvenile solitary confinement: “Growing Up Locked Down: Youth in Solitary Confinement in Jails and Prisons Across the United States” (2012) and “Alone and Afraid: Children Held in Solitary Confinement” (2014).

- Psychological Damage

Mental health experts agree that long term solitary confinement is psychologically harmful for adults – especially those with pre-existing mental illness.8 The effects on children are even more severe due to their unique developmental needs.9

- Increased Suicide Rates

A tragic consequence of the solitary confinement of youth is the increased risk of suicide and self-harm, including cutting and other acts of self-mutilation. According to research published by the Department of Justice, more than 50% of all youth suicides in juvenile facilities occurred while young people were isolated alone in their rooms, and more than 60% of young people who committed suicide in custody had a history of being held in isolation.10

- Denial of Education and Rehabilitation

Access to regular meaningful exercise, to reading and writing materials, and to adequate mental health care – the very activities that could help troubled youth grow into healthy and productive citizens – is hampered when youth are confined in isolation.11 Failure to provide appropriate programming for youth inhibits their ability to grow and develop normally, to access legal services, and to contribute to society upon their release.12

- Stunted Development

Young people’s brains and bodies are developing, placing youth at risk of physical and psychological harm when healthy development is impeded.13 The evidence is undisputed that youth require regular exercise and activity to support growing muscles and bones.14 Additionally, since many children in the juvenile justice system have disabilities or histories of trauma and abuse, solitary confinement can be even more harmful to the child’s future ability to lead a productive life.15

Constitutional and International Law Provide Special Protections for Children

Recent Supreme Court jurisprudence makes clear that youth and adults must be treated differently in the context of crime and punishment. For example, we no longer permit juveniles to be given the death penalty nor life without parole.16 As the United States Supreme Court wrote in abolishing life without parole for juveniles, “…developments in psychology and brain science continue to show fundamental differences between juvenile and adult minds.”17

In addition to these Supreme Court opinions on the difference between youth and adults, there is a growing trend among lower courts in cases specifically regarding juveniles in solitary confinement. For instance, two young men who experienced mental health deterioration while held in solitary confinement in juvenile facilities in New Jersey prevailed against the state in a $400,000 settlement.18 Similar lawsuits have been filed with successful resolutions in Illinois, New York and Ohio.19

International human rights law also distinguishes between youth and adults, mandating that youth who commit crimes receive rehabilitative punishments appropriate to their age and status.20 According to the United Nations Special Rapporteur on Torture, solitary confinement of youth is cruel, inhumane and degrading treatment and in some cases, torture.21

The ACLU’s research in Nebraska shows that Nebraska facilities fail to comply with constitutional and human rights law.

Research in Nebraska

In order to fully evaluate the policies and use of solitary confinement in Nebraska youth detention facilities the ACLU began by identifying current written policies from each facility. Next, the ACLU conduced an open records request, asking each facility to provide logs showing length of stay and frequency of use of solitary for an 18-month period, covering January 2014 through June 2015 in order to evaluate implementation of the policies and actual use of solitary confinement. The findings of this research are outlined in the following pages.

It is important to note at the outset that the Douglas County Youth Center and Scotts Bluff County Detention Center responded to our requests and indicated that they do not even keep time logs which would permit us to calculate the usage rates. This disappointing lack of data in two major youth facilities raises concerns and demonstrates a clear need for meaningful statewide reforms.

Experts do not distinguish between “room restriction” where a juvenile is confined alone in their cell and “solitary confinement” in a special locked unit—the mental health impacts are the same. Our requests from the facilities encompassed all forms of isolation from peers. Some facilities reported they use room restriction for periods, then permit the juvenile to attend classes before placing the juvenile back in room restriction. In contrast, some facilities impose room restriction or solitary confinement without any periods out of isolation. The data below incorporates all isolation as reported by the facilities without differentiation.

Inventory of Nebraska Juvenile Detention Facilities and Solitary Confinement Policies

Nebraska currently has nine juvenile detention centers.

Two state youth centers run by the Department of Health and Human Services

- Youth Rehabilitation and Treatment Center at Kearney - males

- Youth Rehabilitation and Treatment Center at Geneva - females

Two state facilities run by the Nebraska Department of Corrections

- Nebraska Correctional Youth Facility - males

- Nebraska Correctional Center for Women - females

Five county facilities

- Douglas County Youth Center

- Lancaster County Youth Services

- Northeast Nebraska Juvenile Services Center (Norfolk)

- Sarpy County Juvenile Justice Center

- Scotts Bluff County Detention Center

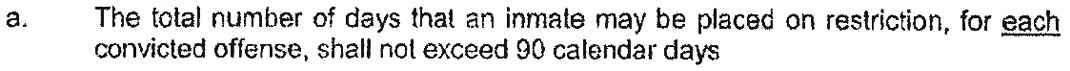

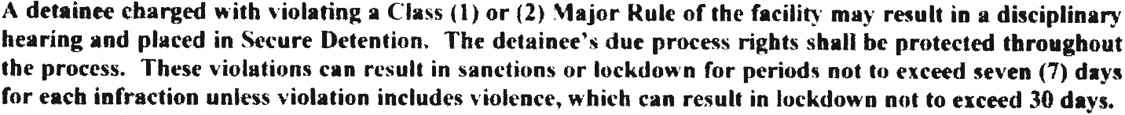

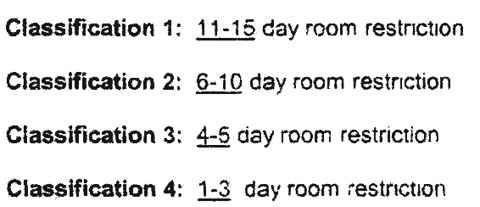

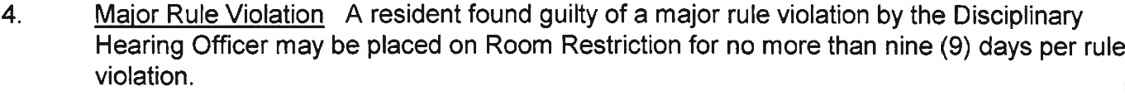

As evidenced in the policy inventory below it is apparent that young people are held in solitary confinement as a form of punishment for major and minor rule violations; they are held in solitary as a safety precaution to protect them from adult inmates; they are held in solitary to promote prison management; and sometimes, they are held in solitary for medical purposes. The myriad of ways a young person can be placed in solitary is accompanied by time limit variations that reflect facility-unique policies. These policies demonstrate a disturbing lack of uniformity at each of Nebraska’s juvenile detention centers.

It should be noted that juveniles in the custody of the Department of Corrections have been adjudicated as adults—but that label does not change the fact they are still under the age of 18 with the same vulnerabilities and ongoing brain development as their counterparts in the custody of DHHS.

Youth Rehabilitation and Treatment Center - Kearney

Youth Rehabilitation and Treatment Center - Geneva

Nebraska Correctional Youth Facility and Nebraska Correctional Center for Women22

Douglas County Youth Center

Lancastser County Youth Services

Northeast Nebraska Juvenile Services Center (Norfolk)

Sarpy County Juvenile Justice Center

Sarpy County has not promulgated any policies which limit time that youth may be subjected to solitary confinement.

Scotts Bluff County Detention Center

Examples of Solitary Confinement Use in Nebraska Facilities

A young Nebraskan’s experience with solitary confinement is completely arbitrary and dependent upon the facility in which he or she is placed. For example, a youth who serves his or her time at the Geneva or Kearney Youth Rehabilitation Center could expect to spend no more than 5 days in solitary confinement, while a youth who spends his time at Nebraska Correctional Youth Facility could expect to spend up to 90 days in solitary confinement for a major rule violation.

Solitary logs from Lancaster County Youth Services demonstrate the seemingly often arbitrary and subjective use of solitary confinement as a form of punishment.

The lack of state-wide standards leaves facilities with far too much discretion, often resulting in the use of solitary confinement for improper or unnecessary purposes. These are among the more trivial reasons a youth has been placed in solitary.

Use of Solitary Confinement in Nebraska Juvenile Facilities

The ACLU conduced an open records request, asking each facility to provide logs showing length of stay and frequency of use of solitary for an 18-month period, covering January 2014 through June 2015.

The Douglas County Youth Center and Scotts Bluff County Detention Center were unable to provide us with data about their use of solitary.

Kearney

|

| State Facility, 2012-2014 |

| Time Served in Solitary (days) |

186 |

| Average Length of Stay in Solitary (hours) |

20.80 |

| Longest Single Stay in Solitary (days) |

5 |

| Shortest Stay in Solitary (hours) |

0.06 |

Geneva

|

| State Facility, 2012-2014 |

| Time Served in Solitary (days) |

54.24 |

| Average Length of Stay in Solitary (hours) |

43.78 |

| Longest Single Stay in Solitary (days) |

5.1 |

| Shortest Stay in Solitary (hours) |

6.17 |

Lancaster

|

| County Facility, 2014-2015 |

| Time Served in Solitary (days) |

455.85 |

| Average Length of Stay in Solitary (hours) |

14.15 |

| Longest Single Stay in Solitary (days) |

10 |

| Shortest Stay in Solitary (hours) |

0.25 |

Sarpy

|

| County Facility, 2014-2015 |

| Time Served in Solitary (days) |

12.18 |

| Average Length of Stay in Solitary (hours) |

1.76 |

| Longest Single Stay in Solitary (days) |

0.43 |

| Shortest Stay in Solitary (hours) |

0.13 |

Nebraska Correctional Youth Facility (in Douglas County)

|

| State Facility, 2014-2015 |

| Time Served in Solitary (days) |

2121.04 |

| Average Length of Stay in Solitary (hours) |

187.66 |

| Longest Single Stay in Solitary (days) |

90 |

| Shortest Stay in Solitary (hours) |

24 |

Northeast NE Juvenile Services Center (in Madison County)

|

| County Facility, 2014-2015 |

| Time Served in Solitary (days) |

1064 |

| Average Length of Stay in Solitary (hours) |

189.16 |

| Longest Single Stay in Solitary (days) |

52 |

| Shortest Stay in Solitary (hours) |

24 |

Jacob was a status offender who was put in the Douglas County Youth Facility on three occasions from the time he was 15 to 17. Read more of his story.

Inventory of Policy Reform Ideas and Solutions

Nebraska can and must do better for our vulnerable youth. Alternatives to solitary confinement produce positive results and less damage to children. As such, this report includes an inventory of best practices and successful models for reform that should be considered by Nebraska policymakers, thought leaders, regulators, and facility managers.

National best practices for managing youth uniformly include strict limitations on the duration of and procedures for placing youth in isolation.23 The American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry recommends that solitary confinement be used only as an immediate safety mechanism.24 The Juvenile Detention Alternatives Initiative narrows that window to only 4 hours.25 This is because the negative effects of the prolonged isolation of youth, whether intended to protect or punish, far outweigh any purported benefits. Indeed, despite its pervasive use and well known harms, prolonged isolation serves no correctional purpose.26 There is no research to support the prolonged isolation of children as a therapeutic tool or to promote positive behavior. In fact, interactive treatment programs are more successful at reducing behavior problems and mental health problems in youth, while isolation provokes and worsens these problems.27

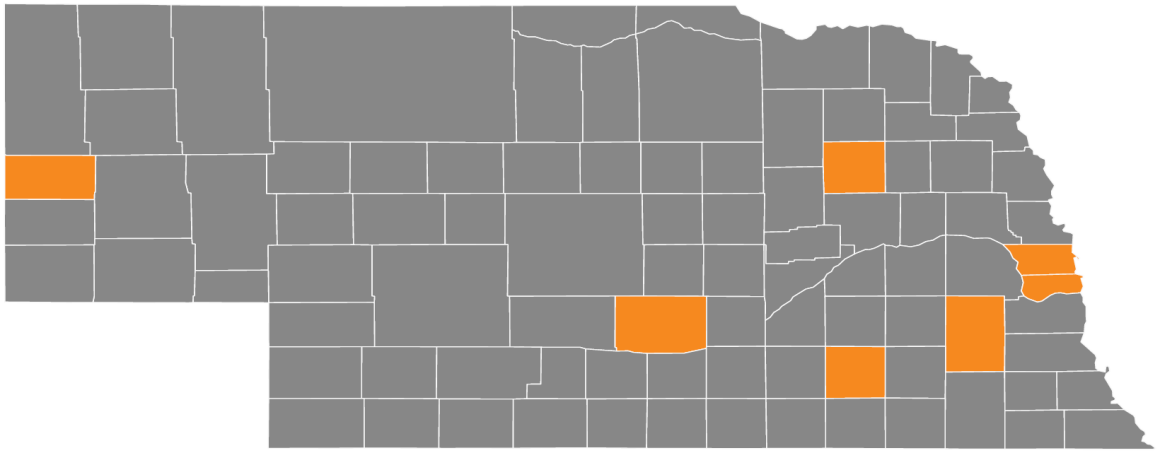

States all across the country are safely and successfully limiting the solitary confinement of juveniles in custody. Reports indicate that state juvenile justice agencies have implemented policy changes in recent years increasingly limiting isolation practices, with a majority of state agencies limiting isolation to a maximum of five days.28 Several of Nebraska’s neighboring states, including South Dakota29, Minnesota30, Iowa31, Missouri32, and Arkansas33 have policies that limit the use of isolation to five days or less. Six states – Alaska34, Connecticut35, Maine36, Nevada37, Oklahoma38, and West Virginia39 – by statute have limited certain forms of isolation in juvenile detention facilities.

In some of these states, lawmakers have passed substantive bans on punitive isolation or on isolation for periods longer than 72 hours. In others, such as Nevada, strict reporting requirements have been implemented, to monitor the system-wide use of isolation. Meanwhile, other states have adopted more systemic models that eliminate the need for isolation. New York, for instance, has moved completely away from using isolation by implementing the “Sanctuary Model,” which emphasizes trauma-informed care in lieu of punitive responses to youth misbehavior.40 Recently, Illinois has taken an important and progressive step in prohibiting solitary confinement of juveniles, as well as implementing policies that tightly limit and regulate any separation of youths from the general population for safety reasons.41

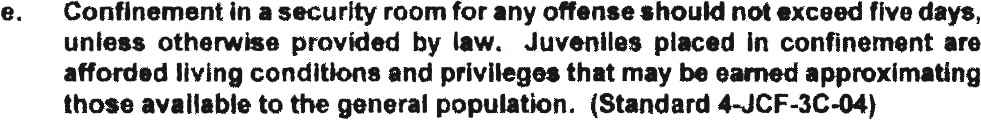

Best practices suggested by the Juvenile Detention Alternatives Initiative and the Performance Based Standards Initiative permit brief periods of isolation as long as they are supervised.42 The American Correctional Association standards would also permit solitary confinement but with approximately equivalent living conditions and privileges including more staff attention rather than less.43

Nebraska policymakers should consider establishing and implementing uniform statewide policies for the use of solitary confinement which can be applied to all our juvenile facilities. As more states begin to move away from solitary confinement for youth, Nebraska should consider banning solitary as well. Establishing clear policies, ensuring strong education and implementation efforts at the agency and facility level, and providing for effective ongoing oversight are critical elements of successful reform. Such legislation could include reforms that place limitations on when and how solitary can be used:

- Solitary confinement is not to be used as a disciplinary measure or as punishment except after all other less-restrictive options have been exhausted, in extreme circumstances, which must be documented, and should not be used for four hours or longer.

- Any juvenile placed in disciplinary or punitive room confinement must be provided due process protections, including the opportunity to know the reason for the decision, to appeal the decision in writing and with an advocate present.

- Solitary confinement of a juvenile for longer than four hours should be approved by the director of the juvenile facility and documented in writing. A mental health professional should also provide an assessment of the youth placed in solitary confinement for over four hours.

- The staff member who authorized the use of seclusion should file a written report with the head of the institution or facility setting forth the circumstances of the action and the reason for the use of seclusion.

- Each juvenile facility should ensure clear documentation regarding the usage of solitary confinement, including all of the following data points:

- The name and age of the person subject to solitary confinement.

- The date and time the person was placed in solitary confinement.

- The date and time the person was released from solitary confinement.

- A description of circumstances leading to use of solitary confinement.

- A description of alternative actions and sanctions attempted and found unsuccessful.

- Mandating that all staff working in youth facilities have training in youth development, mental health, and de-escalation techniques as part of the academy and annual refresher training. Staff need more positive skills to deal with kids, especially kids with backgrounds of abuse and trauma, so part of reform is empowering staff to do their job better.

States that have reformed juvenile solitary

Conclusion

Solitary confinement and isolation of children is psychologically and developmentally damaging and can result in long-term problems and even suicide. Nebraska’s laws, policies, and practices must be reformed to ensure that conditions in the juvenile justice system are effective and safe – and that they prioritize protection and rehabilitation.

Working together we firmly believe that meaningful reforms have the capacity to ensure improved conditions of confinement curing potential constitutional violations for Nebraska youth, mitigation of risk and legal liability for the State and counties which have jurisdiction over juvenile detention facilities, and most importantly improved outcomes for vulnerable children in Nebraska now and well into the future.

Endnotes

1 Solitary Confinement of Juvenile Offenders, American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry (April 2012), https://www.aacap.org/aacap/policy_statements/2012/solitary_confinement_of_juvenile_offenders.aspx.

2 Juvenile Detention Facility Assessment, Standards Instrument: 2014 Update. Juvenile Detention Alternatives Initiative, a project of the Annie E. Casey Foundation.

3 Voices for Children, Data Snapshot: Nebraska’s Youth Rehabilitation and Treatment Centers (2015), available at http://issuu.com/voicesne/docs/yrtc_data_snapshot.

4 Kids Count Data Center, a Project of the Annie E. Casey Foundation: Youth Residing in Juvenile Detention, Correctional and/or Residential Facilities (Oct. 2015), http://datacenter.kidscount.org/data/tables/42-youth-residing-in-juvenil....

5 Nebraska Commission on Law Enforcement and Criminal Justice, Juvenile Court Reporting, http://www.ncc.nebraska.gov/statistics/data_search/jcr.htm (last visited Nov. 18, 2015).

6 Kids Count Data Center, supra note 4, at http://datacenter.kidscount.org/data/tables/42-youth-residing-in-juvenil....

7 Kids Count Data Center, supra note 4, at http://datacenter.kidscount.org/data/tables/8391-youth-residing-in-juven...,1353/16996,17598.

8 Craig Haney, Mental Health Issues in Long-Term Solitary and “Supermax” Confinement, 49 Crime & Delinq. 124, 130, 134 (2003).

9 Solitary Confinement of Juvenile Offenders, American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry (2012), https://www.aacap.org/aacap/policy_statements/2012/solitary_confinement_of_juvenile_offenders.aspx; see also Sandra Simkins, Marty Beyer & Lisa Geis, The Harmful Use of Isolation in Juvenile Facilities: the Need for Post-Disposition Representation, 38 WASH. U. J.L. & POL’Y 241, 257-61 (2012).

10 Id. at 259; see also Christopher J. Mumola, Bureau of Justice Statistics, NCJ 210036, Suicide and Homicide in State Prisons and Local Jails (2005), available at http://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/shsplj.pdf.

11 Andrea J. Sedlak & Karla S. McPherson, Office of Juvenile Justice & Delinquency Prevention, NCJ 22729, Conditions of Confinement: Findings from the Survey of Youth in Residential Placement (2010), available at https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/ojjdp/227729.pdf.

12 Centers for Disease Control, “Effects on Violence of Laws and Policies Facilitating the Transfer of Youth from the Juvenile to the Adult Justice System,” (2007), available at http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/pdf/rr/rr5609.pdf and “The Dangers of Detention,” Justice Policy Institute, (2006), available at http://www.justicepolicy.org/images/upload/06-11_REP_DangersOfDetention_JJ.pdf.

13 American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, supra note 9.

14 Centers for Disease Control & Prevention, How Much Physical Activity do Children Need?, http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/pdf/rr/rr5609.pdf.

15 , Policy Statement: Health Care for Youth in the Juvenile Justice System, 128 PEDIATRICS 1219, 1223-24 (2011), available at http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/pediatrics/early/2011/11/22/peds.2011-1757.full.pdf (reviewing the literature on the prevalence of mental health problems among incarcerated youth);Andrea J. Sedlak, Karla S. McPherson & Monica Basena, Office of Juvenile Justice & Delinquency Prevention, NCJ 240703, Nature and Risk of Victimization: Findings from the Survey of Youth in Residential Placement (2013), available at http://www.ojjdp.gov/pubs/240703.pdf (finding that 56 percent of youth in custody experience one or more types of victimization while in custody, including sexual assault, theft, robbery, and physical assault).

16 Graham v. Florida, 560 U.S. 48 (2010) (outlawing life without parole for juveniles); Roper v. Simmons, 453 U.S. 551 (2005) (outlawing capital punishment for juveniles).

17 Graham v. Florida, at 68.

18 Jeff Goldman, N.J. To Pay Half of $400K Settlement over Solitary Confinement of Juveniles, The Star-Ledger, Dec. 10, 2013.

19 Julie Bosman, Lawsuit Leads to New Limits on Solitary Confinement at Juvenile Prisons in Illinois, , May 5, 2015, at A11. For other lawsuits successfully resolved to limit or ban solitary confinement, see, e.g., Consent Decree, C.B., et al. v. Walnut Grove Corr. Facility, No. 3:10-cv-663 (S.D. Miss. 2012) (prohibiting solitary confinement of children); Settlement Agreement, Raistlen Katka v. Montana State Prison, No. BDV 2009-1163 (Apr. 12, 2012) (limiting the use of isolation and requiring special permission); Mo. Sup. Ct. Rule 129.04 app. A § 9.5-9.6 (2009) (placing limits on “room restriction exceeding twenty-four hours.)” For Ohio litigation, see DOJ Summary of the Case and Settlement, http://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/2014/May/14-crt-541.html; see also Order, United States v. Ohio, No. 2:08-cv-475 (S.D. Ohio, May 20, 2014), available at http://www.childrenslawky.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/Doc-400-1-Agreed-Order.pdf For New York litigation, see Stipulation for a Stay with Conditions, Docket No. 11-CV-2694 (SAS), Peoples v. Fischer, No. 2:11-cv-02694-SAS, Doc. 124 (Feb. 19, 2014 S.D.N.Y.), available at http://www.nyclu.org/files/releases/Solitary_Stipulation.pdf

20 International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, Arts. 10, 14(4), opened for signature Dec. 16, 1966, S. Exec. Rep. 102-23, 999 U.N.T.S. 171 (entered into force Mar. 23, 1976) (ratified by U.S. June 8, 1992) (“ICCPR”); Convention on the Rights of the Child, Arts. 3(1), 37, 40(3)-(4), opened for signature Nov. 20, 1989, 1577 U.N.T.S. 3 (entered into force Sept. 2, 1990) (“CRC”). The United States signed the CRC in 1995 but has not ratified the treaty.

21 Special Rapporteur on Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, Interim Rep. of the Special Rapporteur on Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, ¶ 77, U.N. Doc. A/66/268 (Aug. 5, 2011) (by Juan Mendez), available at http://solitaryconfinement.org/uploads/SpecRapTortureAug2011.pdf

22 While theoretically young women adjudicated as adults will be housed in York at the women’s prison, there are few young female detainees at any given time so this report’s statistics only reflect the young men in custody at the Nebraska Correctional Youth Facility.

23 See, e.g., American Correctional Association, “Performance Based Standards Juvenile Correctional Facilities” (4th ed. 2009); Performance Based Standards Learning Institute, “PbS Goals, Standards, Outcome Measures, Expected Practices and Processes” (2007), available at http://sccounty01.co.santa-cruz.ca.us/prb/media%5CGoalsStandardsOutcome%20Measures.pdf; Juvenile Detention Alternatives Initiative, “A Guide to Juvenile Detention Reform: Juvenile Detention Facility Assessment” (2014) at 117, available at http://www.prearesourcecenter.org/sites/default/files/library/aecf-juveniledetentionfacilityassessment-2014.pdf (“Staff never use room confinement for discipline, punishment, administrative convenience, retaliation, staffing shortages, or reasons other than a temporary response to behavior that threatens immediate harm to a youth or others”).

24 American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, supra note 9.

25 Voices for Children, supra note 3.

26 See, e.g., Linda M. Finke, RN, PhD, Use of Seclusion is Not Evidence-Based Practice, 14 J. Child & Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing 4, (2001), available at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1744-6171.2001.tb00312.x/full; Steven H. Rosenbaum, Chief, Special Litigation Section, Remarks before the Fourteenth Annual National Juvenile Corrections and Detention Forum (May 16, 1999), available at http://www.justice.gov/crt/special-litigation-section-cases-and-matters-1

27 Simkins et al., supra note 9, at 257-58.

28 , Reducing Isolation and Room Confinement, at 4-6 (Sept. 2012), available at http://pbstandards.org/uploads/documents/PbS_Reducing_Isolation_Room_Confinement_201209.pdf. (“…very few state agency policies permit extended isolation time for youths and the majority limit time to as little as three hours and a maximum of up to five days.” at 4).

29 South Dakota Department of Corrections: Juvenile Discipline System, available at http://doc.sd.gov/documents/about/policies/Juvenile%20Discipline%20System.pdf

30 Minnesota Department of Corrections: Discipline Plan and Rules of Conduct, available at http://www.doc.state.mn.us/DocPolicy2/html/DPW_DisplayINS.asp?Opt=303.010RW.htm.

31 Iowa Administrative Code: Juvenile Detention and Shelter Care Homes, available at https://www.legis.iowa.gov/docs/ACO/chapter/441.105.pdf

32 Missouri Standards for Operation of Juvenile Detention Facility, available at https://www.courts.mo.gov/file/AppendixA-JuvenileDetentionStandards02-14.pdf

33 Arkansas Juvenile Detention Facility Standards, available at http://www.sos.arkansas.gov/rulesRegs/Arkansas%20Register/2014/dec2014/006.26.14-002.pdf

34 Alaska Delinquency Rule 13 (Oct. 15, 2012) (banning isolation of juveniles for “punitive” reasons, but defining “secure confinement” as permissible for “disciplinary” reasons and when there is a safety or security risk).

35 Conn. Gen. Stat. Ann. § 46b-133 (d)(5) (officials supervising children who have been arrested may not place “any child at any time” in “solitary confinement,” but the statute does not define “solitary confinement”); Conn. Gen. Stat. Ann. § 17a-16(d)(1) (West 2014); Conn. Agencies Regs. § 17a-16-11 (2014) (for post-adjudication youth in Connecticut, the use of “seclusion” is governed by a statute and corresponding regulations requiring periodic authorizations and thirty-minute checks).

36 Me. Rev. Stat. tit. 34-A § 3032 (5) (including segregation in the list of permissible punishments for adults, but not in the list for children; however, while state law prohibits “confinement to a cell” and “segregation” as punishment in juvenile correctional facilities, the state’s rules permit “room restriction” for juveniles, evevn for minor rule violations).

37 Nev. Rev. Stat. § 62B (children may be subjected to “corrective room restriction” only if all other less-restrictive options have been exhausted and only for listed purposes, and no child may be locked alone in a room for longer than 72 hours).

38 Okla. Admin. Code, 377:35-11-4, Solitary Confinement (noting that solitary confinement of youth is a “serious and extreme measure to be imposed only in emergency situation”).

39 W.V. Code §49-5-16a, Rules governing juvenile facilities (solitary confinement may not be used to punish a juvenile and except for sleeping hours, a juvenile may not be locked alone in a room unless that juvenile is “not amenable to reasonable direction and control.”); but see W.V. Div. Juvenile Serv., Pol’y No. 330.00, Institutional Operations, at 9, available at http://www.wvdjs.state.wv.us/Portals /0/Files/330.00%20-%20Resident%20Discipline.pdf (permitting up to ten days room confinement as a sanction for some offenses).

40 See , The Sanctuary Model, http://www.sanctuaryweb.com/network.php (listing systems and facilities that have adopted the Sanctuary Model for juvenile justice).

41 Illinois Department of Juvenile Justice, Discipline and Grievances, available at http://www.aclu-il.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/RJ-v-Jones-IDJJ-confinement-procedures-filed-4-20-15.pdf

42 , supra note 28, at 4-6.

43 American Correctional Association, Performance Based Standards Juvenile Correctional Facilities 51 (4th ed. 2009) (Standard 4-JCF-3C-01).

Table of Solitary Confinment Use in Nebraska Juvenile Facilities

| |

Time Served in Solitary (days) |

Average Length of Stay in solitary (hours) |

Longest Single Stay in Solitary (days) |

Shortest Single Stay in Solitary (hours) |

| Lancaster (County Facility) |

| |

455.85 |

14.45 |

10.00 |

0.25 |

| 2014 |

314.55 |

14.92 |

10.00 |

0.25 |

| 2015 |

141.30 |

13.51 |

7.00 |

0.50 |

| Sarpy (County Facility) |

| |

12.18 |

1.76 |

0.43 |

0.13 |

| 2014 |

6.39 |

1.60 |

0.43 |

0.13 |

| 2015 |

5.80 |

1.99 |

0.42 |

0.13 |

| Northeast NE Juvenile Services Center (County Facility) |

| |

1064.00 |

189.16 |

52.00 |

24.00 |

| 2014 |

1064.00 |

189.16 |

52.00 |

24.00 |

| Nebraska Correctional Youth Facility (County Facility) |

| |

2721.04 |

187.66 |

90.00 |

24.00 |

| 2014 |

1179.04 |

179.09 |

28.00 |

48.00 |

| 2015 |

1542.00 |

194.78 |

90.00 |

24.00 |

| Kearney (State Facility) |

| |

186.00 |

20.80 |

5.00 |

0.06 |

| 2012 |

120.31 |

5.00 |

7.44 |

23.17 |

| 2013 |

48.79 |

3.50 |

0.06 |

23.49 |

| 2014 |

17.15 |

2.55 |

0.67 |

15.73 |

| Geneva (State Facility) |

| |

54.24 |

43.78 |

5.10 |

6.17 |

| 2012 |

40.43 |

5.10 |

24.27 |

83.33 |

| 2013 |

7.61 |

1.89 |

8.42 |

26.42 |

| 2014 |

6.20 |

1.99 |

6.17 |

21.58 |

Date

Monday, January 4, 2016 - 10:00am

Featured image

Show featured image

Hide banner image

Override default banner image

Override site-wide featured content

End Solitary Confinement for Young Nebraskans

Related issues

Smart Justice

Documents

Show related content

Pinned related content

As a teen, all I wanted was my friendships and relationships back.

ACLU Finds Dangerous Overuse of Solitary Confinement for Nebraska Youth

Tweet Text

[node:title]

Type

Style

Standard with sidebar