School officials and politicians have often tried to remove books from public schools and public libraries because they disagree or disapprove of the content or viewpoint expressed in such books. This practice, called book banning, is the taking of books and materials from a classroom or library, making it difficult or impossible for students or library patrons to access these materials. This is censorship and it restricts intellectual freedom. The American Library Association defines intellectual freedom as “the right of every individual to both seek and receive information from all points of view without restriction. It provides for free access to all expressions of ideas through which any and all sides of a question, cause or movement can be explored.” As book bans continue to sweep the nation, it’s critical to be aware of the tools available to fight against this form of government censorship.

The First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution as well as the Nebraska Constitution prohibit the government from making books or ideas unavailable based on content or expressed viewpoint. The U.S. Supreme Court has stated that “local school boards may not remove books from school library shelves simply because they dislike the ideas contained in those books….” Board of Education, Island Trees Union Free School District no. 26 v. Pico, 457 U.S. 853, 872 (1982). Additionally, the First Amendment right to receive information is “vigorously enforced in the context of a public library.” See Sund v. City of Wichita Falls, 121 F. Supp. 2d 530, 547 (N.D. Tex. 2000). Courts have ruled that a public library is a limited public forum and in a public forum, the government’s ability to restrict First Amendment rights is extremely narrow such that it cannot restrict speech in a discriminatory manner. Jaffe v. Baltimore Cty. Bd. of Library Trustees, 2009 WL 7083368 at *4 (D. Maryland 2009); Kreimer v. Bd. of Police for Town of Morristown, 958 F.2d 1242, 1259 (3d Cir. 1992); Neinast v. Bd. of Trustees of Columbus Metro. Libr., 346 F.3d 585, 591 (6th Cir. 2003). Put simply, book banning is unconstitutional; yet, attacks on books are on the rise.

This Book Banning Toolkit aims to equip you with information, action steps, talking points and more as you fight to protect the freedoms guaranteed to you by the Bill of Rights. We thank you for joining the fight against censorship.

FAQs:

1. What kinds of books are most often targeted in attempts to ban books?

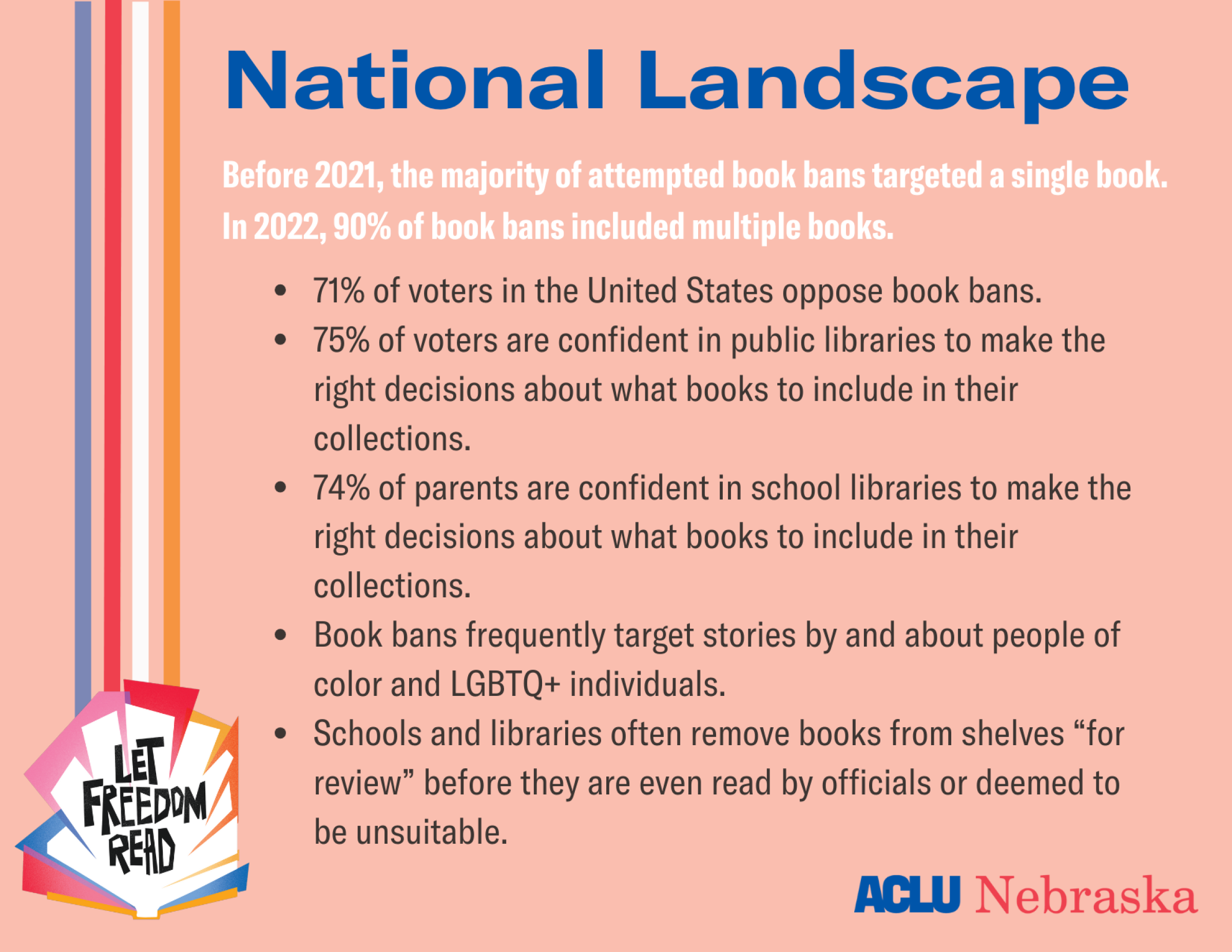

People who want to ban books target a variety of books, but the current trend is to target materials chronicling the experiences of marginalized people. School boards often remove books authored by or regarding people of color and LGBTQ+ individuals, claiming that the books are not suitable for young people. But young readers frequently look to these books for a sense of belonging or to learn about other perspectives. Those who seek to ban books base their fears on alleged moralistic biases; they want to impose their ideals by repressing other viewpoints. Consequently, their actions and censorship compound feelings of isolation in young readers searching for critical confirmation that their experiences and feelings are valid.

2. Hasn’t the U.S. Supreme ruled on this issue already?

Government actors, including school boards and local public officials, are strictly forbidden from regulating speech based on its content. Courts have outlined the extent of the right to receive information in the context of public schools and libraries. In Tinker vs. Des Moines Independent Community School District, the Supreme Court clarified that students and teachers do not “shed their constitutional rights” when they enter a school. 393 U.S. 503, 506 (1969). Further, in Board of Education, Island Trees Union Free School District no. 26 v. Pico, the Supreme Court held that schools cannot “remove books from school library shelves simply because they dislike the ideas contained in those books and seek by their removal to proscribe what shall be orthodox in politics, nationalism, religion, or other matters of opinion.” 457 U.S. 853, 872 (1982) (quoting W. Virginia State Bd. of Educ. v. Barnette, 319 U.S. 624, 642 (1943)). As discussed above, First Amendment principles also apply in the context of public libraries. “The policy of the First Amendment favors dissemination of information and opinion, and the guarantees of freedom of speech and press were not designed to prevent the censorship of the press merely, but any action of the government by means of which it might prevent such free and general discussion of public matters as seems absolutely essential.” Bigelow v. Virginia, 421 U.S. 809, 829 (1975).

3. Shouldn’t parents be able to control what their children are reading?

Parents can decide whether they want their children to read certain materials but should not be permitted to unilaterally decide what is available to others. For every parent that objects to a book, there will be others that support it. Parents can control what information their own children have access to, but controlling the information that all children have access to amounts to privileging the moral beliefs of some individuals over others.

4. Shouldn’t readers be protected from harmful ideas?

Books that contain harmful viewpoints, such as racism depicted in Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird, are critical for understanding important historical context and the current systemic racism issues affecting Black, Indigenous, and people of color. This is particularly important in K-12 public schools which are to meant protect the “marketplace of ideas” as America’s “nurseries of democracy.” Mahoney Area Sch. Dist. v. B.L. by & through Levy, 141 S. Ct. 2038 (2021); Axson, at 1293 (10th Cir. 2004) (quoting Settle v. Dickson Cty. Sch. Bd., 53 F.3d 152, 155 (6th Cir. 1995)).

5. What is a book “challenge”?

Those who wish to get a book or books banned begin the process by “challenging” a book, usually by raising it as an issue at a school board meeting or by contacting local officials and complaining. Some public schools or public libraries may have policies in place for challenging materials or books. Often, public school boards or public library administrators will direct librarians to remove the books from the shelves while they conduct a review. While review processes differ, there are typically review committees along with opportunities for public comment at school board or city council meetings. Books that are deemed “unsuitable” are then fully removed from the public library or public school, and at that point are “banned.”

6. What can I do to combat book bans and challenges to books?

See the action items below for more details about what you can do to combat censorship.

Action Items

- Talk about book bans

- One of the most impactful things that you can do is have conversations about book banning. Tell your friends, family, and community members about the attacks on books and why it’s important for information to remain unrestricted.

- Contact your local officials.

- Local officials (your mayor, city council members, school board members, librarians, etc.) are often in the best position to protect books.

- Contact your local officials and tell them how you feel about book bans. Encourage them to be cautious and to keep in mind that the vocal minority does not speak for everyone.

- Use the talking points below to help draft your email, letter, or testimony.

- Contact your state senator.

- The Nebraska Legislature can pass laws that provide additional protections for books and access to information. They can also attempt to pass laws that restrict access to information in public schools or public libraries.

- Over the last recent legislative sessions, some state senators have introduced bills that attempt to ban certain materials from public schools and require that schools obtain prior parental approval for materials found in classrooms and libraries.

- You can write to your senator and encourage them to oppose current and future legislation designed to censor books and materials in public spaces.

- You can use this website to find your senator and their contact information. https://nebraskalegislature.gov/senators/senator_find.php.

- Use the talking points below to help draft your email, letter, or testimony.

- Attend school board and city council meetings.

- These meetings are typically the battlegrounds for book bans. While it is understandably intimidating to attend meetings, it is absolutely critical for school boards to understand and listen to your opinion.

- Attend these meetings and share your thoughts. Why is it important to you that books remain in the library? How will the removal of books affect readers in your community?

- Encourage other community members to attend meetings with you and to share their thoughts.

- Join a book reviewing committee.

- Many school districts employ community members to judge challenged books via book review committees.

- Contact your local school board and ask to be a part of book reviewing processes.

- Start a banned book club.

- Books are meant to be read and banned books are no different. A book club centered around banned books can be a great way to start important conversations.

- You can organize with your community members to periodically meet and discuss banned books.

- Stay informed.

- Follow ACLU and ACLU of Nebraska on social media to stay up to date on book banning information.

Talking Points

These talking points can be used in general discussions about book banning. They may also be helpful for contacting state senators, school boards, the Nebraska Department of Education, and others in combatting censorship. When writing to government officials, it is often best to start by introducing yourself with details such as where you live, how long you have lived in Nebraska, and whether you are a constituent of the elected official to whom you are writing.

• All students have a right to read and learn free from censorship.

• All students have a First Amendment right to read and learn about the history and viewpoints of all communities — including their own identity — inside and outside of the classroom.

• Book bans and classroom censorship efforts work to effectively erase the history and lived experiences of women, people of color, and LGBTQ+ people, censoring discussions about race, gender, and sexuality that impact people’s daily lives.

• The First Amendment protects the right to share ideas, including educators’ and students’ right to receive and exchange information and knowledge.

• Freedom of expression protects our right to read, learn, and share ideas free from viewpoint-based censorship.

• Book bans in public schools and public libraries — places that are central to exploring ideas, encountering new perspectives, and learning to think for ourselves — are misguided attempts to try to suppress important rights.

• All young people deserve to see themselves — and the issues that impact them — reflected in their classrooms and their books.

• All students benefit from access to inclusive teaching, where students can freely learn and talk about the history, viewpoints, and the ideas of all communities in this country.

• Every student has the right to receive an equitable education and to have open and honest conversations about America’s history.

Acknowledgment: Carter Matt, University of Illinois College of Law, Class of 2024